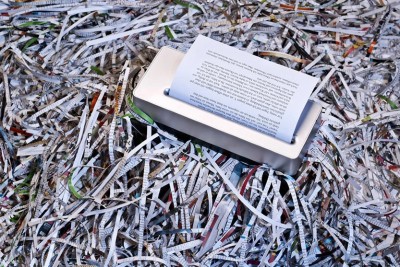

The number of retracted papers has been rising over the past few years.Credit: Priscila Zambotto/Getty

Many universities and research institutions around the world prize high productivity. They encourage researchers to publish more articles and accrue more citations; higher counts can signal that an institution’s research is impactful and push its international ranking up. Overall, most published articles and citations represent reliable contributions to the scientific record. But in some cases, the push for more, faster research comes at a cost: it can encourage sloppy science, plagiarism and research falsification and fabrication.

For a long time, such problematic work went mostly undetected. But over the past decade, a growing cohort of research-integrity sleuths have been checking the text, images and data of scientific articles. They have found flaws in what’s estimated to be hundreds of thousands of papers. That, in turn, has led many publishers to scrutinize their own processes, resulting in a rise in retracted research: some 0.2% of articles published in 2022 are now retracted, a rate that’s triple what it was a decade ago.

These universities have the most retracted scientific articles

Although retractions can be the result of discovering an honest mistake and are a necessary part of the scientific process, the vast majority of papers are withdrawn for dishonesty or fraud, according to the site Retraction Watch, which maintains a public database of retractions. Many sleuths say that, if all problematic research were retracted, the rate would be much higher. But even those retractions that have occurred are proving useful beyond correcting the scientific record: they are becoming the basis of their own kind of research-integrity alarm.

A news feature in Nature this week contains an original analysis by Nature’s news team of the institutions around the world that have the most retracted research and the highest retraction rates. The analysis used data from research-integrity firms, which have created their own data sets of retracted papers, building on Retraction Watch and other online sources, as part of software that helps to identify signatures of fake or flawed work.

Some of these tools help publishers to identify red flags in submissions, such as whether authors of a manuscript — or, in some cases, their affiliated institutions — have previously had misconduct-associated retractions (such tools ignore the minority of retractions issued through honest error). Another red flag is whether a paper heavily cites already-retracted work.

More than 10,000 research papers were retracted in 2023 — a new record

To carry out its analysis, Nature asked three firms — Scitility, based in Sparks, Nevada; Research Signals in London; and Digital Science, also in London — to provide their data on retraction rates by institution (Digital Science is a part of Holtzbrinck Publishing Group, the majority shareholder in Nature’s publisher, Springer Nature). Nature then cleaned and compared the data.

The analysis reveals that certain hospitals in China come to the fore in retraction rates, and that retraction volumes at certain institutions in Saudi Arabia and India have risen over the past half decade. Pinpointing such hotspots for retractions can shine a light on why bad science is happening.

In many cases, the retractions were linked to many authors at an institution, not to one or two bad apples. This suggests that, although individual researchers are ultimately responsible for their misconduct and mistakes, there might be perverse incentives at those institutions — or countries — that promote that behaviour.

An awareness of indicators such as retraction rates and retraction volumes could prompt institutions to examine and change their incentives. Instead of counting only articles and citations, institutions could start considering retraction rates too, a kind of counter-metric in a metric-obsessed world. These metrics could also be considered in rankings, or by funders.

Care is needed in using these data. Examining retraction rates by institution or country could unfairly taint authors who work at those places. There’s also the concern that focusing on just these metrics might be misleading: lots of retractions, or a high retraction rate, might reflect intense scrutiny rather than worse behaviour.

Thousands of highly cited scientists have at least one retraction

In general, there is little consistency in how publishers record and communicate retractions — although last year, publishers did agree, under the auspices of the US National Information Standards Organization, on a unified technical standard for doing this, which might help to improve matters.

Retraction Watch is to be commended for pushing hard to improve how retractions are recorded, and for creating a relatively clean database of retractions on which further tools and analyses, including those used in Nature’s analysis, can be built. But Nature did find some incorrect institutional assignments in the data provided by the firms marketing the existing analysis tools — as is almost inevitable in such large data sets. (The firms say that they are working to correct the errors).

Online records of retracted work are messy, too. For instance, one heavily cited paper in The Lancet is currently categorized as retracted in CrossRef, a site that records data about published articles, when it has in fact only been corrected. This was because of an error by the paper’s publisher, Elsevier (Elsevier did not respond to a request for comment).

Still, the new mountain of retractions data is a valuable tool that should not be ignored. Retractions data are a reminder that quality, as well as quantity, count in science.