Children in India were taught in open-air schools during the COVID-19 pandemic.Credit: Amarjeet Kumar Singh/Anadolu Agency/Getty

Growing up in India, economist Abhijit Banerjee was always intrigued by the impressive mental arithmetic skills of young people working in the stalls at the local fruit and vegetable markets. “I used to tag along with my grandfather” to these markets and “I could see kids … who could do the mathematics involved”, he told the Nature podcast. “You could buy five things and then give them some money and they would give you the correct change back, you know, quite complicated calculations.” Through his work in India, Banerjee, who is based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Cambridge, revealed that these same young people are doing poorly in tests of mathematical proficiency similar to those that determine their success at school and beyond. The results indicate that maths education must broaden its scope and approaches to serve all — especially the talented and hard-working children from lower-income families. The question is: how?

School smart or street smart? Maths skills of children in India tested

Maths education is becoming ever more important worldwide. Written assessments are set to become more complex as countries adapt their schools’ curricula to meet the needs of our increasingly data-rich world, incorporating data and computational literacy along with conventional textbook maths. Proficiency in the kind of maths assessed in written exams is key to careers in computing, engineering, mathematics and science. A sound grasp of principles of mathematical reasoning is also necessary for other professions and for many life skills.

In practice, a student leaving school today would ideally need to know, perhaps using basic algebra and statistics knowledge, how to interpret the infographics that fill their social-media feeds. They should have some understanding of coding principles, even if they haven’t written code themselves. And they need to be familiar with, if not be proficient in using, spreadsheets and other programs.

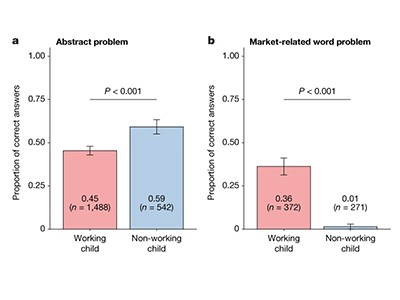

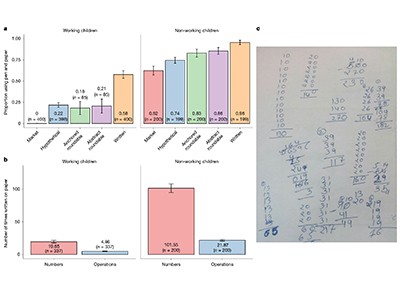

Innovative approaches are needed to ensure that children benefit from such education. In a study published last week, Banerjee, economist Esther Duflo at MIT, psychologist Elizabeth Spelke at Harvard University in Cambridge and their colleagues compared the maths proficiency of two groups of young people under the age of 18 years in India (A. V. Banerjee et al. Nature https://doi.org/n5xz; 2025). Both groups attended school, but one group also worked in markets. The researchers found that the working group was more proficient in mental arithmetic than the other one. Yet, those who worked performed poorly in standard written tests of arithmetic problems, such as doing long division.

Read the paper: Children’s arithmetic skills do not transfer between applied and academic mathematics

The results reveal both the power of learning-by-doing and its pitfalls. This method doesn’t automatically lead to success in existing written tests. To do better, these children need help with mathematical reasoning, to complement their rapid mental addition and subtraction skills. Moreover, if a student is already struggling with written assessments in long division and algebra, telling them that they need to learn how to do statistics and use coding programs, such as Python, will not yield the desired outcomes.

Better teaching is crucial, but worldwide, there’s a shortage of trained maths teachers. Changing that and improving how mathematics is taught should be a top priority for education systems, says mathematician and educator Marcus du Sautoy at the University of Oxford, UK.

There are, however, several obstacles that need to be overcome to achieve this, as studies, including those by science-education researcher Jonathan Osborne at Stanford University in California, have shown (C. D. Wilson et al. J. Res. Sci. Teach. 61, 38–69; 2024). The first is that many if not most standard assessment systems globally do not reward an understanding of reasoning — that is, how a particular result was arrived at (the stories behind the maths and science). They reward a mastery of the method and an ability to get the right answer. Second, relatively few teachers are skilled at teaching reasoning and describing maths through storytelling, and of those, even fewer teach students from low-income families.

These obstacles and others must be overcome. It will require big-picture thinking, assessment of the latest research and action from all those involved in maths-education policy. Banerjee and his colleagues have shone a much-needed light on a reservoir of underappreciated talent. With the right guidance, these children could one day be working in research laboratories, establishing start-up companies — and becoming the maths teachers that their countries so desperately need, not least to help future generations to achieve their full potential.