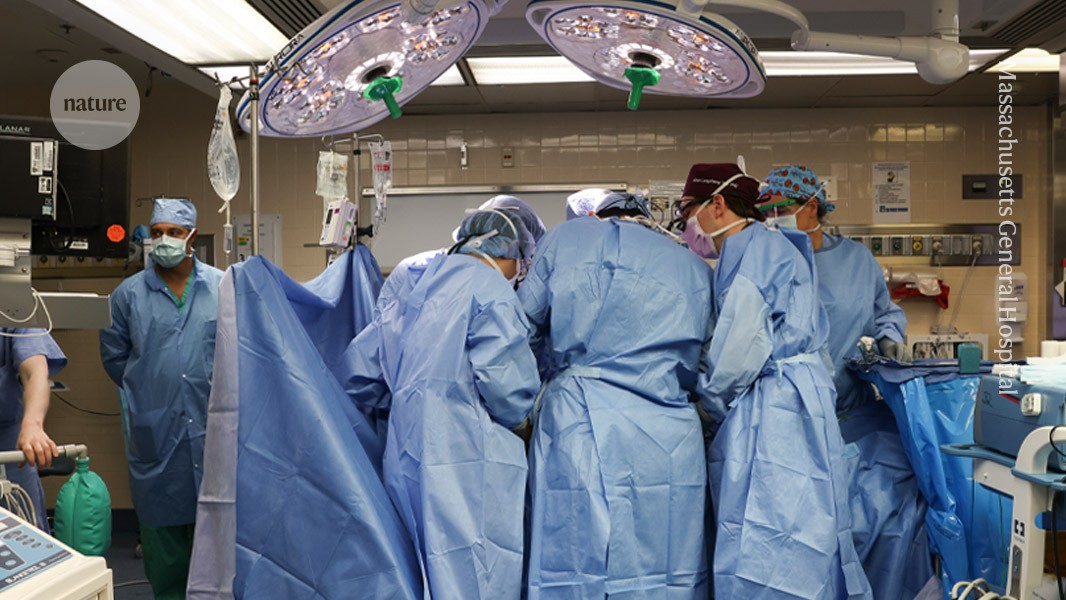

Surgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston transplanted a modified pig kidney into a living person for the first time in 2024.Credit: Massachusetts General Hospital

The first clinical trial testing whether pig kidneys can be safely transplanted into living people has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). As part of the trial, which will begin later this year, kidneys from genetically modified pigs will be transplanted into people with chronic kidney disease whose organs no longer function independently.

Will pigs solve the organ crisis? The future of animal-to-human transplants

The FDA’s greenlight will bring the experimental procedure a step closer to one day supplying organs to the thousands of people who are waiting for a donor organ. “The start of formal clinical trials is very exciting,” says Jay Fishman, a specialist in transplant infectious diseases at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

About half a dozen people in the United States and China have received organs from genome-edited pigs — kidneys, hearts, liver and a thymus — but the surgeries were approved on compassionate grounds, meaning the patients were very sick and had no other options. Most recipients did not survive beyond a few months after the transplants for various reasons, including that they were too sick to cope with major surgery.

“The humans who have received xenotransplants have made a tremendous contribution to our field,” Fishman says. But formal clinical trials are standardized, and can therefore produce important information, including crucial safety and efficacy data, to move the field forwards, he says.

First trial

Six individuals will initially be enrolled in the trial, according to United Therapeutics, the biotechnology firm, based in Silver Spring, Maryland, and Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, that is running the trial. The trial will include people with end-stage kidney disease, aged 55–70 years old, who are not eligible for conventional kidney transplantation for medical reasons or are not likely to get one in the next five years and will possibly die waiting. Patients will be closely monitored for about six months for serious adverse events, infectious diseases and signs of kidney damage, and then followed up with for the rest of their lives.

First pig kidney transplant in a person: what it means for the future

The trial will assess efficacy by tracking how many participants — and transplanted kidneys — survive the procedure, and for how long. It will also measure how well the kidneys filter blood and track changes in the participants’ quality of life.

The FDA has mandated pauses between patients to make sure there are no surprises, Fishman says. A monitoring committee will review safety and efficacy data for the first six participants, before deciding whether the trial should be expanded to up to 50 individuals.

Trials will enable researchers to select people who are in better health than those first compassionate-use recipients to assess the transplant’s safety and efficacy, says Muhammad Mohiuddin, a surgeon and researcher at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore.

The success of this trial will pave the way to longer-term, larger clinical trials, says Wayne Hawthorne, a transplant surgeon at the University of Sydney in Australia.

Mohiuddin, who in 2022 led the first pig-heart transplant into a living person, says he is in the process of submitting a request to the FDA to start clinical trials, but he adds that the heart is a more difficult organ to get approval for.

Another company, eGenesis in Cambridge, Massachusetts, has also submitted a request to the FDA to launch a xenotransplant trial, says Fishman, who has advised both United Therapeutics and eGenesis on microbiology safety and would be involved in an eGenesis trial should it be approved. In an e-mailed statement, eGenesis said that in December, it had received FDA approval to conduct three pig-kidney transplants under compassionate use. The company did not comment on the status of its clinical-trial application.