Brine pools in Chile’s Atacama Desert contain lithium.Credit: Cristobal Olivares/Bloomberg/Getty

Nations are moving away from energy supplied mainly by fossil fuels to using renewable sources, but this transition relies on devices that we all take for granted: batteries. Humanity needs more of them and quickly, especially for electric vehicles, which use up most available battery power. In 2016, the global inbuilt battery capacity in all electric vehicles was around 50 gigawatt hours. By 2023, that figure had surged to almost 800 gigawatt hours. And, by 2035, according to one scenario considered by the International Energy Agency, it could be at least ten times that in 2023 — assuming that countries meet their fossil-fuel reduction pledges (see go.nature.com/4avqdax).

The rechargeable battery is not as new as many might surmise; it is, in fact, more than 150 years old. The first such device was a lead-acid battery, invented in 1859 by French physicist Gaston Planté. The technology was used to power the first electric cars that were developed at the turn of the twentieth century. The battery’s descendants are still providing electrical charge to petrol and diesel engines.

Today, lithium is the element of choice in the weighty boxes that power electric vehicles. The lithium-ion rechargeable battery isn’t a spring chicken either: materials scientists John Goodenough, Stanley Whittingham and Akira Yoshino developed the device in the 1970s and 1980s (although they had to wait until 2019 to receive a Nobel prize for the breakthrough).

Small is beautiful

Lithium is the smallest metallic atom in the periodic table under ambient conditions, and the lightest of the alkali metals. This means that it can carry a lot of electric charge for its size, and that the element can be found in lots of places, from mineral deposits to salty water.

Ten years left to redesign lithium-ion batteries

The United States Geological Survey estimates that the known sources of lithium globally comprise around 105 million tonnes, of which 28 million tonnes can be extracted economically with current technologies (see go.nature.com/4hshays). That could be around a century’s worth of battery supplies. The global annual demand for lithium is around 200,000 tonnes today, although it is projected to increase sevenfold by 2040, the International Energy Agency says (see go.nature.com/4jabduz).

Having an ample supply is good news. But the bad news is that most of the known accessible lithium deposits are found in just a few countries. Although Australia is currently the world’s largest producer of lithium, about half of the world’s known reserves are contained in salt flats in the ‘lithium triangle’ on the borders of Chile, Bolivia and Argentina. China also has considerable reserves.

Extracting lithium from these sources is an energy-intensive process. Large amounts are needed to pump water from its source into huge ponds, where the water evaporates, leaving behind salts. These salts are further processed and separated to obtain lithium-rich minerals.

All stages of the process use considerable quantities of fresh water, often in arid locations, where this resource is scarce. Up to two million litres of water are needed to extract a tonne of lithium, according to some estimates.

An obvious alternative is to obtain lithium from brines, such as seawater; the element is abundant in the world’s oceans. But at 0.1–0.2 parts per million, extracting the metal from these sources is challenging technically and, as is the case for lithium mining, it also has a considerable environmental footprint.

Lithium extraction from low quality brines

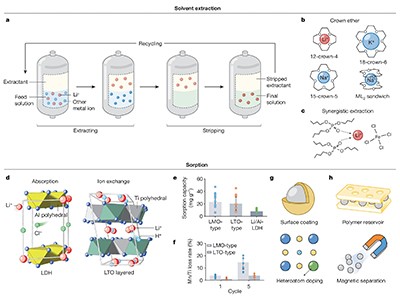

For these reasons, brines are not considered a dependable source. But, as materials scientists Ping He, Haosheng Zhou and their colleagues at Nanjing University in China explain in a Review article in Nature, there are ways to improve existing methods of separating lithium from lower-quality sources, such as developing chemicals that grab lithium more effectively or using special filters and electricity that can separate it out (S. Yang et al. Nature 636, 309–321; 2024).

The good news is that several techniques, from improved filters to better precipitation methods, are being developed to do just that. However, to fully exploit lower-quality lithium sources, the authors say, research needs to go back to the basics of understanding how low concentrations of tiny ions can be separated, and then build back up to improve on the technologies currently being developed.

Researchers are also examining alternatives to lithium, including sodium. The element sits directly below lithium in the periodic table, has similar chemical properties and is easier to source, but its atoms are heavier.

Extraction is only one part of the story. When it comes to the full process of producing lithium batteries, only one country has worked out what to do at scale: China’s government and companies have invested heavily in all stages of electric-vehicle development, including batteries. This is partly to satisfy domestic demand: more than half of new vehicles are electric.

Although the nation is responsible for mining around 20% of the world’s lithium, it refines almost 60%. When it comes to making lithium-ion battery components, China is responsible for making more than 80% of each battery part used globally. Other countries need to work out how they too can access this crucial energy source.

The final part of the picture is to improve the batteries themselves. Battery performance must be enhanced; they need to last longer and be fully or mostly recyclable. In all respects, lithium is the key.