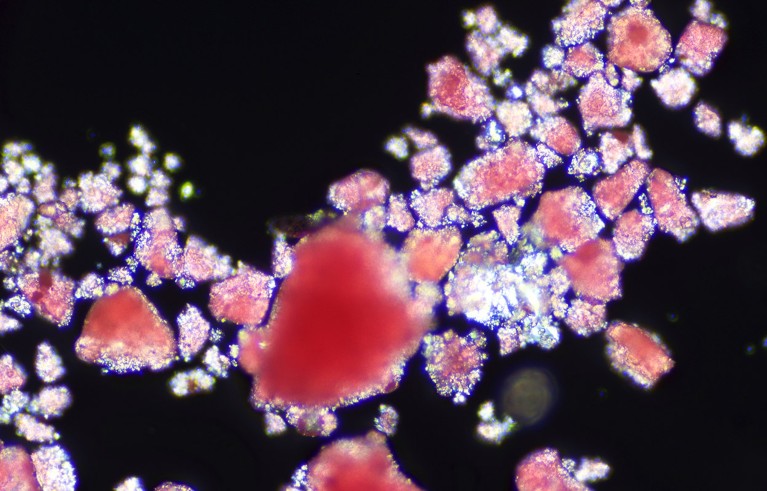

Tiny pieces of plastic were found lodged in blood vessels in the brains of mice.Credit: Sinclair Stammers/Science Photo Library

For the first time, scientists have tracked microplastics moving through the bodies of mice in real time1. The tiny plastic particles are gobbled up by immune cells, travel through the bloodstream and eventually become lodged in blood vessels in the brain. It’s not clear whether such obstructions occur in people, say researchers, but they did seem to affect the mice’s movement.

Microplastics are specks of plastic, less than 5 millimeters long, that can be found everywhere, from the deep ocean to Antarctic ice. They are in the air we breathe, the water we drink and the food we eat. They can even enter our bloodstreams directly through plastic medical devices.

Studies show that microplastics, and smaller nanoplastics, have made their way into humans’ brains, livers and kidneys, but researchers are just beginning to understand what happens to these plastic intruders and their effect on human health. One study last year, for example, found that people with micro- and nano-plastics in fatty deposits in their main artery were more likely to experience a heart attack, stroke or death2.

‘Car crash’

In the latest study, published in Science Advances today, Haipeng Huang, a biomedical researcher at Peking University in Beijing, and his colleagues wanted to better understand how microplastics affect the brain. They used a fluorescence imaging technique called miniature two-photon microscopy to observe what was happening in mouse brains through a transparent window surgically implanted into the animal’s skull.

The imaging technique can trace microplastics as they move through the bloodstream, says Eliane El Hayek, an environmental-health researcher at University of New Mexico in Albuquerque. “It’s very interesting, and very helpful.”

The researchers gave mice water laced with fluorescent spheres of polystyrene, a popular product used to make appliances, packaging and even toys. About three hours later, fluorescent cells appeared. Further investigation suggested that immune cells known as neutrophils and phagocytes had ingested the bright plastic specks. Some of these cells probably got trapped in the tight curves of tiny blood vessels in an area of the brain called the cortex. More plastic-packed cells would sometimes pile on — “like a car crash in the blood vessels”, says Huang. Some obstructions eventually cleared, but others remained for the four-week observation period.

When the researchers injected the plastic spheres into the mice intravenously, they observed the glowing cells within minutes. Smaller particles resulted in fewer obstructions.