Credit: Keystone/Zuma Press/Alamy

Andrew V. Schally’s most enduring legacy lies in his groundbreaking discovery of brain hormones that regulate the pituitary gland. Located below the hypothalamus, the gland produces, stores and releases several hormones. It also controls the function of other glands. Schally’s identification of hypothalamic hormones upended our understanding of the endocrine system and the treatment of hormone-dependent conditions. His work on these peptides — small proteins that can serve as messengers in the body — earned him the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1977. He shared the honour with Rosalyn Yalow and Roger Guillemin for their independent contributions to the field. Schally has died, aged 97.

Born in 1926 in Wilno, Poland, (now Vilnius in Lithuania), Schally’s early years were marked by hardship, surviving Nazi-occupied eastern Europe and spending part of the Second World War in Romania. In 1945, he journeyed through Italy and France to settle in the United Kingdom. After receiving a secondary-school diploma in Scotland, he went to London, where he studied chemistry. His endocrinology journey began in 1949, when he joined the National Institute for Medical Research in London as a research assistant. There, he worked with Charles Harington, the director of the institute and a pioneering biochemist who had analysed the chemical constitution of the thyroid hormone thyroxine.

Forget lung, breast or prostate cancer: why tumour naming needs to change

In 1952, Schally’s passion for mammalian physiology led him to McGill University in Montreal, Canada, where he obtained a bachelor’s degree in 1955 and a PhD in 1957. He joined the ranks of those studying the long- and short-range effects of hormones, as well as the factors that affected their release, laying the foundation for his lifelong dedication to understanding the intricate interface between brain function and endocrine activity.

In 1957, Schally joined Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas. There, he collaborated with Roger Guillemin on research on the hypothalamus, and particularly its role in self-regulating processes (homeostasis). Although their relationship later became contentious, the affiliation drove both investigators to achieve remarkable scientific breakthroughs. Schally was determined to identify the structure of thyrotropin-releasing factor (TRF), which is secreted by the hypothalamus to regulate the release of thyrotropin from the anterior pituitary gland. Thyrotropin stimulates the thyroid gland to produce thyroid hormones, which regulate nearly every aspect of the body’s metabolic activity.

Isolating the delicate TRF molecule in the brain while maintaining its active conformation posed huge challenges, casting doubt on the initial findings. But Schally stood firm in his observations on TRF and his hypotheses about how other hypothalamic hormones can regulate the anterior pituitary’s function. A pivotal moment came in 1961, during Schally’s visit to Uppsala University in Sweden to see biochemist Jerker Porath. There, he gained valuable experience in the use of the filtration gel Sephadex and column electrophoresis, which would prove crucial in isolating the TRF.

Mind-reading devices are revealing the brain’s secrets

A year later, Schally established a research group at Tulane University in New Orleans, Louisiana, and the New Orleans VA Medical Center. With unwavering faith and patience, he meticulously followed the demanding steps of the isolation process, overcoming the immense challenge of extracting increasingly pure materials from a crude hypothalamic extract. He yielded 800 micrograms of peptide from 160,000 pig hypothalami and provided conclusive evidence that the brain controls hormonal secretions in the body. In 1969, Schally and Guillemin independently isolated TRF and identified its structure. Their studies provided experimental confirmation of the relationship predicted by the UK physiologist Geoffrey Harris in the 1940s.

In 1971, Schally doubled his efforts and successfully identified the luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LH-RH), the peptide that regulates the release of luteinizing hormone from the anterior pituitary gland, triggering ovulation and stimulating the secretion of progesterone and oestrogen from the ovaries.

His development and innovative use of LH-RH agonists and antagonists — agents that mimic or block LH-RH — provided less-invasive and more-effective alternatives to conventional treatments for cancers that require hormones to grow, such as prostate and breast tumours.

Decades-long bet on consciousness ends — and it’s philosopher 1, neuroscientist

In 2005, Schally relocated his laboratory from New Orleans to the Miami VA Medical Center and the University of Miami in Florida. His research turned to growth hormone-releasing hormone (GH-RH) agonists and antagonists, which had shown potential in treating various cancers and cardiovascular and inflammatory diseases.

Schally left a lasting impact on medical science and those around him. Lab staff and colleagues enjoyed his famous ‘Schally’s special gin and tonic’ at his residence. He was an avid swimmer in the Atlantic Ocean even in his later years, notwithstanding various lifeguards’ objections to his swimming far out from the shore at Miami Beach.

After the COVID-19 pandemic, Schally continued to work from his home in Florida, reviewing and writing manuscripts and savouring conversations about lab results. Often, discussions would bring up old manuscripts and references, and he would always know exactly where each paper was in his cabinet. This mastery of both the scientific and historical progress of the field of hypothalamic hormones and peptides made him an effective research director and mentor.

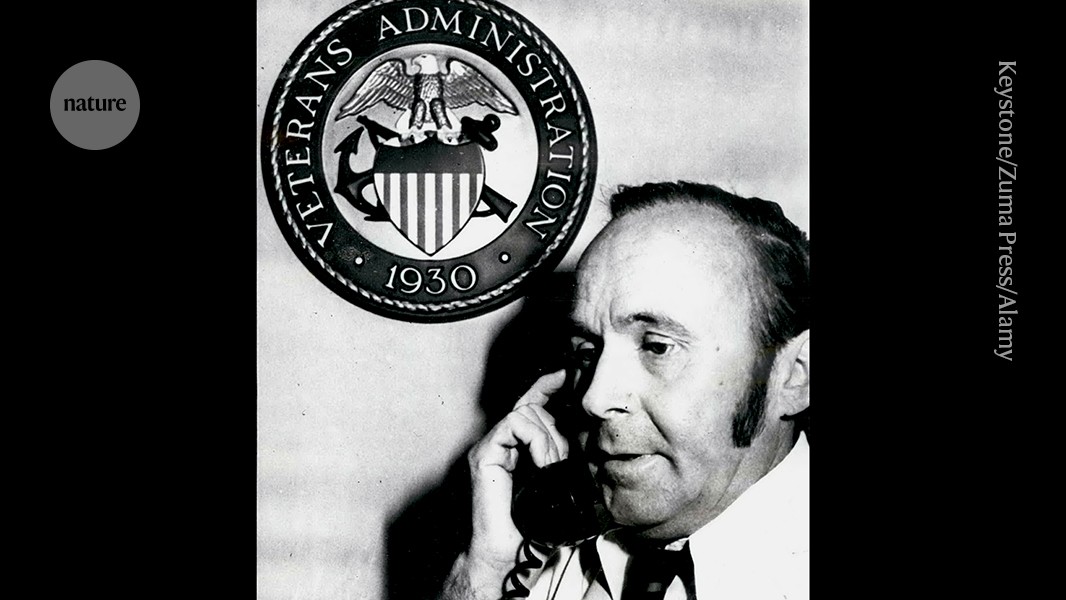

Schally was dedicated to advancing health care, particularly for veterans. He devoted 62 years to conducting research at the US Department of Veterans Affairs until his final years. His dedication continues to inspire investigators who build on his pioneering work.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.