Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Fossilized faeces samples revealed dinosaurs’ changing diets.Credit: Grzegorz Niedzwiedzki

By analysing fossils of poo and vomit, researchers have reconstructed what dinosaurs ate and how this changed over time. The findings give a better understanding of how dinosaurs became so dominant, revealing that their rise, over millions of years, was influenced by factors including climate change-induced shifts in what vegetation was available, which the dinosaurs were able to adapt to better than other animals. The contents of the fossils became more varied over time, suggesting that larger dinosaurs with more diverse feeding habits began to gain prominence in the late Triassic period a little over 200 million years ago.

Two teams of physicists at the CERN particle physics lab are planning to transport antimatter out of the lab for the first time next year. Antimatter is difficult to create and extremely short-lived, because it instantly annihilates on contact with matter. Both excursions will be short journeys across the CERN campus in specialized containers on the back of a van. One project plans to use antimatter to probe the nuclear structures of other short-lived materials. The other aims to move antiprotons to a location free from experimental noise, where they can be examined in finer detail.

Data from Aditya-L1, India’s first solar-observation mission, has allowed researchers to estimate the precise time of a coronal mass ejection (CME), the expulsion of a huge fireball of charged particles from the sun’s corona. CMEs can knock down power grids on Earth and wreak havoc on the electronics of satellites, affecting global communications. Real-time information on the timing and trajectory of CMEs could forewarn engineers and allow them to take protective countermeasures.

Features & opinion

Researchers are generating knowledge at an unprecedented rate, but it is not all being stored safely for the future in digital archives. A lack of funding, infrastructure and expertise lies at the core of the issue, notes a Nature editorial. “It is not just about creating backup copies of things,” says Kathleen Shearer of the Confederation of Open Access Repositories, a global network of scholarly archives. “It is about the active management of content over time in a rapidly evolving technological environment.”

Reference: Journal of Librarianship and Scholarly Communication paper

US president-elect Donald Trump has pledged to roll back his country’s commitment to international climate action, but “whether this exit breaks or merely bends the Paris agreement will depend on how the rest of the world responds”, writes political scientist David Victor. Other countries “must band together to show what ‘we are still in’ means in practice… they should lay out concrete actions with observable outcomes”. Ultimately, given Trump’s policies, a US exit from the agreement could be beneficial, he argues. “It would remove US diplomats from the meetings, preventing their political briefs and their nation’s refusal to cooperate with the rest of the world from sowing chaos.”

After a missile attack close to her home in Sumy, Ukraine, sustainable-development researcher Olena Melnyk knew it was time to flee the country to keep her family safe. Since then, she has been working in Zurich, Switzerland, where she is investigating the war’s impacts on Ukraine’s soil with her colleagues back home. Managing a team in a warzone requires flexibility and finding opportunities to meet in person. Doing science during a conflict also takes tenacity. “Even if it’s a terrible situation, don’t give up,” says Melnyk.

Olena Melnyk at the Salisbury Plain military training area, UK, testing a soil-sampling protocol for use in bomb craters.Credit: Mark Horton

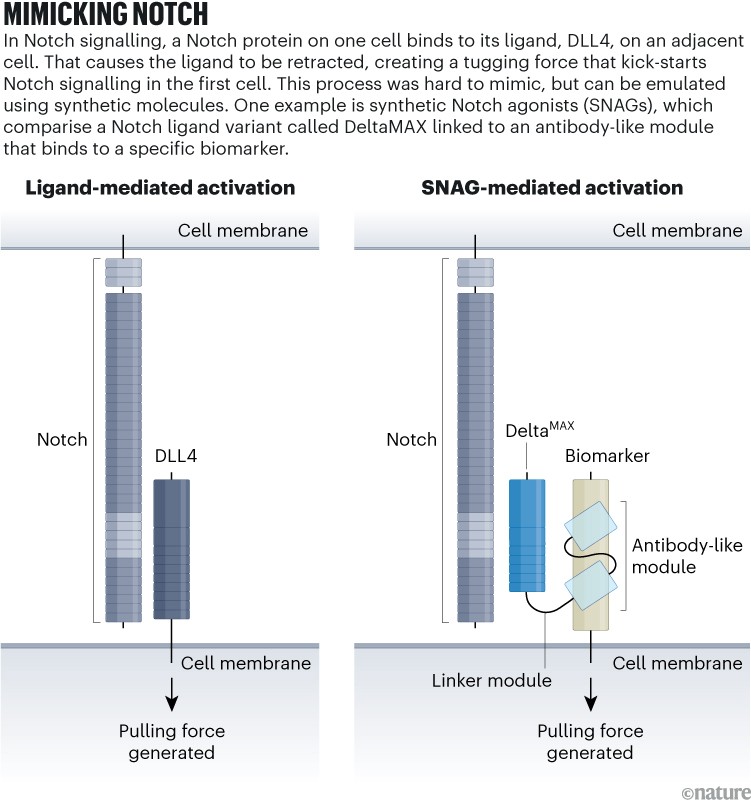

Infographic of the week

Source: Adapted from ref. 2

Notch — a family of protein receptors — plays a crucial part in bodily processes from embryonic development to cell differentiation. Mimicking Notch signalling in experiments requires a pulling force to expose an inner part of the receptor, making it almost impossible to exploit in the clinic. Now, Notch research has reached “a turning point”, says immunologist Juan Carlos Zúñiga-Pflücker. Researchers unveiled not one but two new soluble tools to activate the pathway at a conference in July. (Nature | 6 min read)

References: bioRxiv preprint 1 & preprint 2 (not peer reviewed)

Today I’m enjoying a case of scientific serendipity: two research groups have solved the mystery of which gene causes orange fur in cats at the same time. The two groups, one in the US and one in Japan, discovered that ginger, tortoiseshell and calico cats are all missing a non-coding DNA sequence that might regulate a fur-colour-coding gene, giving them their brightly coloured coats. In recognition of their joint discovery, the teams decided to publish their preprints at the same time.

Help us solve any mysteries in this newsletter by sending your feedback to [email protected].

Thanks for reading,

Jacob Smith, associate editor, Nature Briefing

With contributions by Flora Graham and Gemma Conroy

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma