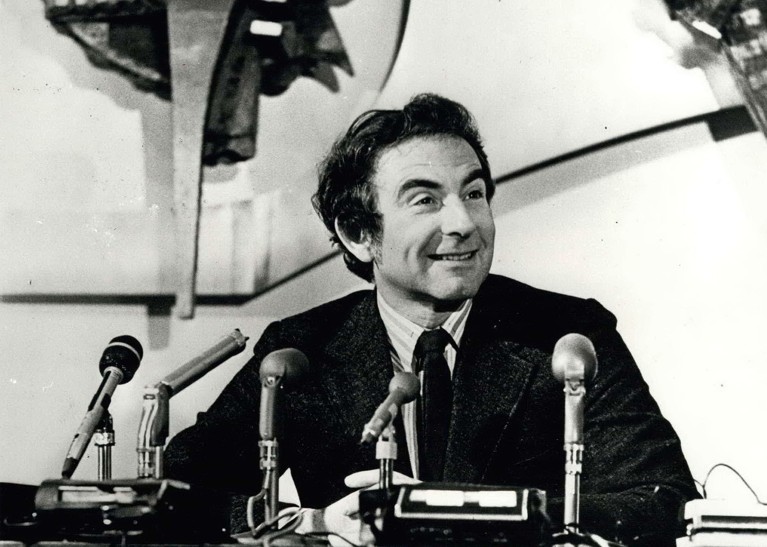

Credit: Keystone Press/Alamy

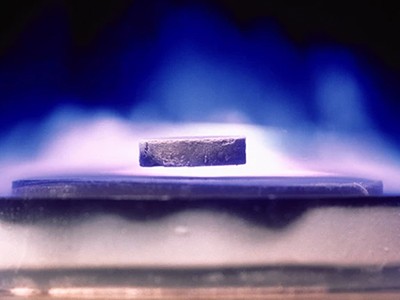

Leon Cooper, who has died aged 94, helped to solve a problem that had stumped many of the greatest minds in twentieth-century physics. With his colleagues John Bardeen and Robert Schrieffer, he deciphered the dance of electrons that causes superconductivity, or the sudden drop in electrical resistance experienced by certain materials, such as mercury, when they reach temperatures only a few degrees above absolute zero. This phenomenon has since served to generate, for example, the very high magnetic fields needed to operate technology such as magnetic resonance imaging body scanners. The Bardeen–Cooper–Schrieffer (BCS) theory of superconductivity won them the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1972.

Having worked out one of the hardest problems in physics, Cooper turned his attention to neuroscience. With his graduate students Elie Bienenstock and Paul Munro, he developed a model — inevitably dubbed the Bienenstock–Cooper–Munro (BCM) theory to mirror the BCS theory — of changes in the strength of the neuronal connections in the brain as individuals learn.

His pioneering theoretical work on neural networks places him in the company of other physicists such as John Hopfield and Geoffrey Hinton — winners of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Physics who developed algorithms that could represent the process of learning in a model of a very small volume of brain tissue.

Cooper (originally Kupchik) was born in New York City, the son of Jewish immigrants from Belarus and Poland. After his mother died, he and his sister spent part of their childhood in care. In 1947, he graduated from the Bronx High School of Science, which has produced six other Nobel laureates in physics. He then studied physics at Columbia University, New York City, completing a PhD in 1954.

Why superconductor research is in a ‘golden age’ — despite controversy

He joined the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, for a year, before Bardeen recruited him to the University of Illinois at Champaign–Urbana, to work together on problems of condensed-matter theory and specifically on superconductivity. “The long and very imposing list of physicists (among them [Niels] Bohr, [Werner] Heisenberg and [Richard] Feynman) who had tried or were trying their hand at superconductivity should have given me pause,” recalled Cooper in a later memoir. Feynman had even said that anyone trying to tackle superconductivity would soon discover that they were “too stupid to solve the problem”.

Superconductivity was first observed in 1911, but by the mid-1950s it was still unknown how electrons could flow seemingly without limit in supercooled mercury. Some suggested that new physics — an undiscovered kind of particle, for example — might be needed to account for the phenomenon. Working for more than a year with every theoretical tool at his disposal, Cooper proposed that faint vibrations in lattices of atoms at low temperatures prompted electrons to pair up instead of repelling one another. All of these ‘Cooper pairs’ could in turn operate as a single entity and pass through the lattice unopposed.

Mathematical analysis by Schrieffer supported the theory, which Bardeen refined. Their paper caused a sensation (J. Bardeen et al. Phys. Rev. 108, 1175; 1957); it was subsequently confirmed by experiment. The same phenomenon also underlies the performance of more recently discovered ‘high-temperature superconductors’, which reach a resistance-free state at up to 100 degrees above absolute zero. “The great thing that Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer showed was that no new particles or forces had to be introduced to understand superconductivity,” wrote Steven Weinberg, a theoretical physicist who won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1979.

How would room-temperature superconductors change science?

In 1958, Cooper moved to Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, where he remained for the rest of his working life. In 1974, he founded the Institute for Brain and Neural Systems there, recruiting a team to research the connectivity underlying cognitive function. The group built on the work of pioneers such as brain researchers Warren McCulloch and Walter Pitts of the University of Illinois at Chicago, who had published a mathematical model of a neural network in 1943 (W. S. McCulloch and W. Pitts, Bull. Math. Biophys. 5, 115–133; 1943), and of the Canadian psychologist Donald Hebb, whose 1949 book The Organization of Behavior proposed that, if neurons repeatedly fire — that is, send electrical signals — to the body and brain at the same time, the synapses between them become stronger.

The BCM theory, published in 1982, addressed how specific cells in the visual cortex become selective for certain stimuli, such as an edge at a particular angle, depending on previous visual experience. It proposed that, the more often incoming signals activated a neuron, the higher the threshold for its activation would become, and vice-versa. This sliding threshold has the effect of stabilizing the responsiveness of the neuron, making it either more or less active. Cooper’s goal was to model how living brains work, and the BCM theory has stood the test of time. It has also played a part in the development of machine learning. Cooper and his collaborators went on to apply insights from machine learning to many other fields, such as sonar detection.

Although he formally retired in 2014, Cooper never lost his curiosity. That year, he published a collection of essays, Science and Human Experience, based on his lively interest in physics, neuroscience, philosophy and how these fields interacted with each other. He argued that science emerged from a uniquely human desire to explain the world that surrounds us, and that imagination was a crucial part of the process. “Our imagination is marvellously free,” he wrote, “capable of any juxtaposition, unbounded by logic or experience.”

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.