A March for Science rally in Massachusetts. This year, public trust in scientists edged up over 2023 levels, a survey has found. Credit: Brian Snyder/Reuters

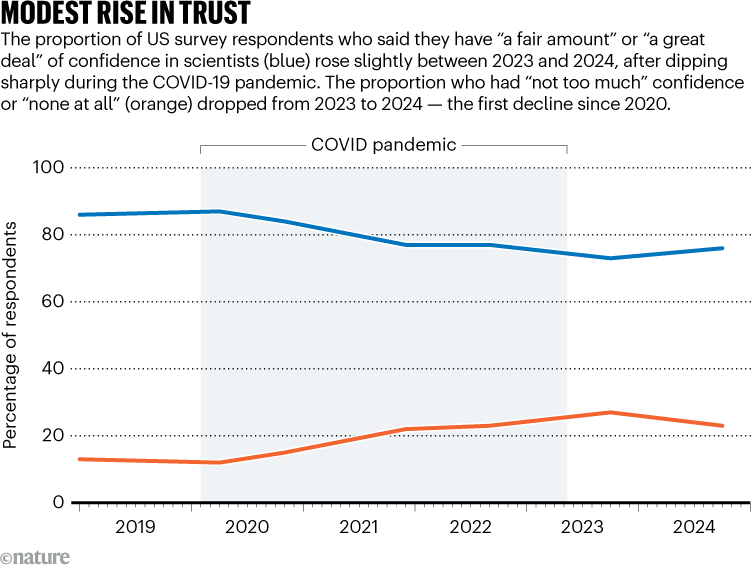

For the first time since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, trust in scientists has increased in the United States — but just slightly, according to a poll conducted two weeks before the US presidential election.

The survey, released today by the Pew Research Center in Washington DC, found that the proportion of those polled who believe that scientists act in the best interests of the public rose from 73% a year ago to 76% now (see ‘Modest rise in trust’). That’s still lower than the 87% who trusted scientists in April 2020, shortly after lockdowns began. But it marks a new shift “away from the declines in trust in science that we saw during the pandemic”, says Alec Tyson, the lead author of the report and an associate director of research at the Pew centre.

Source: Pew Research Center

The findings add to other data that are good news for researchers. A survey of more than 70,000 people in 67 countries in 2022 and 2023 found overall high levels of trust in scientists, according to a preprint posted on the OSF server in January1.

“There is no data to support the argument for a general crisis of trust in science,” says Naomi Oreskes, a science historian at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and a co-author of the preprint. She adds that the Pew results are “very reassuring for the scientific community”.

Some scientists fear that the 5 November re-election of Donald Trump, who has dismissed climate change and disparaged federal scientists, to the US presidency will erode public trust in science — and might signal a rift between scientists and some factions of the US public.

Researchers don’t yet know how political change affects public opinion towards scientists, says Niels Mede, a science-communication researcher at University of Zurich in Switzerland, and a co-author of the preprint. But the timing of the Pew survey means it could be used as a benchmark for tracking attitudes towards science during Trump’s second term, he says.

Partisan split

Tyson and his colleagues polled 9,593 US residents using online and phone surveys between 21 and 27 October. Participants were asked to indicate how much they agreed with statements about scientists’ intelligence, communication skills, compassion for the public and engagement in policy.

Almost 90% of survey respondents who identified themselves as Democrats indicated a belief that scientists act in the public’s best interest. The figure for Republicans was 66% — 5 percentage points higher than last year. But respondents were sharply divided over whether scientists should engage in policy debates on scientific issues, with 51% supporting an active role and 48% saying scientists should stay out of these debates.

How can scientists make the most of the public’s trust in them?

This means that “people want to trust the science but are not always sure they can trust the scientists” to put personal biases aside when using their influence, says Arthur Lupia, a survey researcher at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

The Pew report also found that only 45% of respondents think scientists are good communicators and 47% think scientists feel superior to others. Researchers who spoke to Nature say that the scientific community should accept that feedback, and act on it.

“It’s one thing to discover something — it’s another thing to explain it effectively,” Lupia says. “For science to have public value, we actually have to do both of those things.”

To solve the communication conundrum, Oreskes says that scientific degree programmes should add more public-focused writing and speaking to their curricula. Mede suggests that scientists attend children’s school science fairs, help with community-science projects and find other ways to speak to people face-to-face.

“There is an important opportunity here for scientists, particularly those in government agencies,” says Oreskes, “to do an honest review of the ways in which their communications fell short during the pandemic, and consider how they can do better going forward.”