Whenever we go online, we might find ourselves part of an experiment — without knowing it. Digital platforms track what users do and how they respond to features. Increasingly, these tests are having real-world consequences for its participants.

I’ve seen this in my own research on the gig economy, studying job-listing platforms that offer paid tasks and jobs to freelancers (H. A. Rahman et al. Acad. Mgmt. J. 66, 1803–1830; 2023). Platforms experimented with using different methods for scoring people’s work, as well as changing how their skills would be listed on their profile page and how they could interact with their contractors. These changes affected people’s ratings and the amount of work they received.

How to harness AI’s potential in research — responsibly and ethically

Twenty years ago, such experimentation was transparent. Gig workers could opt in or out of tests. But today, these experiments are done covertly. Gig workers waive their rights when they create an account.

Being experimented on can be disconcerting and disempowering. Imagine that, every time you enter your office, it has been redesigned. So has how you are evaluated, and how you can speak with your superiors, but without your knowledge or consent. Such continual changes affect how you do and feel about your job.

Gig workers expressed that, after noticing frequent changes on the listing platforms that were made without their consent, they started to see themselves as laboratory rats rather than valued users. Because their messages were blocked by chatbots, they were unable to speak to the platform to complain or opt out of the changes. Frustration flared and apathy set in. Their income and well-being declined.

This is concerning, not only because of how affects gig workers, but also because academics are increasingly becoming involved in designing digital experiments. Social scientists follow strict Institutional Review Board (IRB) procedures that govern the ethics of experiments involving people — such as informing them and requiring consent — but these rules don’t apply to technology companies. And that’s leading to questionable practices and potentially unreliable results.

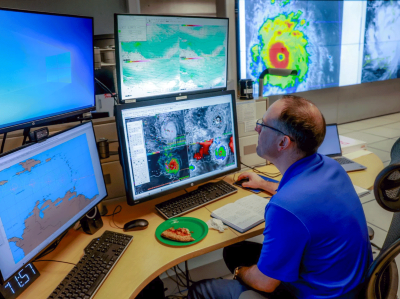

AI to the rescue: how to enhance disaster early warnings with tech tools

Technology companies use their terms of service to authorize them to collect data without any obligation to inform people that they were involved, or provide any opportunity for them to withdraw. Thus, digital experimentation faces scant oversight.

Given that technology companies reach millions of people, experiments using their data can be informative. For example, a 2022 study by academics and the career platform LinkedIn answered questions about how weak links in people’s social networks contribute to job outcomes (K. Rajkumar et al. Science 377, 1304–1310; 2022). The platform varied the algorithm it uses to suggest new contacts for more than 20 million users. Those people were unaware, despite this potentially affecting their job prospects.

Scientists themselves can be subject to such hidden practices. For example, in September, the journal Science acknowledged that studies it had published exploring political polarization using user feeds from the social-media platform Facebook were compromised when the technology giant changed its algorithm during the study period without the scientists’ knowledge (H. Holden Thorp and V. Vinson Science 385, 1393; 2024).

Academics must be more wary about the data that they generate through collaborations with technology companies and rethink how they conduct this research. An ethically robust framework is needed for science–industry collaboration to ensure that experimentation does not jeopardize public trust in science.

Chain retraction: how to stop bad science propagating through the literature

First, scholars should engage in a thorough ethics check by auditing potential partners and making sure that they follow IRB principles. They could work with or create intermediary watchdog organizations, just as Fairwork, based in Oxford, UK, safeguards gig-workers’ rights, which can audit experimentation practices and introduce transparency into data collection. They can diffuse and enforce ethical norms of experimentation, inform industry partners on how to conduct ethically sound research and hold them to account.

Second, scholars need to evaluate the social effects of experimentation to study and mitigate any potential harm. This is not trivial, because experiments rarely consider the well-being of participants and don’t assess potential unintended consequences.

Technology companies should establish their own internal review boards, which have the authority to assess and vet experiments. Industry needs to instil a culture of ethically robust experimentation, including understanding the potential adverse effects participants might face.

Regulation is crucial. One good example is the European Union’s Artificial Intelligence Act, which centres consumers’ right to data privacy and protection and aims to establish “a safe and controlled space for experimentation”.

Consumers and users should form third-party organizations, similar to the unions used by gig workers, to rate companies on whether they request consent and allow people to opt out of experimentation, and how transparent they are.

Driving forward the frontier of science–industry experimentation requires practices, rules and regulations that ensure mutually beneficial outcomes for people, organizations and society.

Competing Interests

The author declares no competing interests.