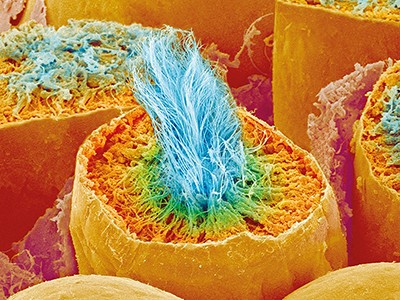

A trio of proteins helps a sperm (artificially coloured) to dock to an egg.Credit: D. Phillips/Science Photo Library

An artificial-intelligence tool honoured by this year’s Nobel prize has revealed intimate details of the molecular meet-cute between sperm and eggs1.

The AlphaFold program, which predicts protein structures, identified a trio of proteins that team up to work as matchmakers between the gametes. Without them, sexual reproduction might hit a dead end in a wide range of animals, from zebrafish to mammals.

The finding, published 17 October in Cell, unravels the previous notion that just two proteins — one on the egg and one on the sperm — would be sufficient to ensure fertilisation, says Enrica Bianchi, a reproductive biologist at the University of Rome ‘Tor Vergata’, who was not involved in the study. “It’s not the old concept of having a key and a lock to open the door anymore,” she says. “It’s more complicated.”

A mysterious union

Despite its critical role in reproduction, the fusion of egg and sperm in vertebrates is a molecular mystery that has proved difficult to crack. The union of the two cells involves proteins that reside in greasy membranes and that are hard to study using standard biochemical methods. The interactions between these proteins are often weak and fleeting, and it is difficult to harvest enough eggs and sperm from some of researchers’ favourite laboratory animals, including mice, for extensive experiments.

Stopping sperm at the source

As a result, early studies of reproductive biology often focused on marine invertebrates that release copious quantities of egg and sperm into water. “If you take a textbook off the shelf and look up fertilisation, you’ll read all about sea urchins,” says Gavin Wright, a biochemist at the University of York, UK, who was not involved in the study. “It’s a tricky thing to research.”

To overcome the supply problem, Andrea Pauli, a molecular biologist at the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology in Vienna and her colleagues, began their work in zebrafish, a vertebrate that also releases its eggs and sperm into the surrounding water. And to bypass the difficulties of working with membrane proteins in the laboratory, the team used AlphaFold to predict interactions between protein s. Two of AlphaFold’s developers were awarded the Nobel Prize for chemistry on 9 October.

Not two but three

AlphaFold predicted that three sperm proteins work together to form a complex. Two of these proteins were previously known to be important for fertility. Pauli and her colleagues then confirmed that the third is also critical for fertility in both zebrafish and mice, and that the three proteins interact with one another.

The team also found that, in zebrafish, the trio creates a place for an egg protein to bind, providing a mechanism by which the two cells could recognize one another. “It’s a way to say, ‘Sperm, you found an egg’ and ‘Egg, you found a sperm’,” says Andreas Blaha, a biochemist at the Research Institute of Molecular Pathology and co-author of the paper.

The findings might one day yield a way to screen people struggling with infertility, to find out whether problems with this complex could be the cause, says Wright.

And the results highlight a role for AlphaFold in studying fertilisation, he adds. “We’re limited in terms of experiments,” he says. “It might be that these modelling studies have an important role to play in the future.”