Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are bearing the brunt of climate change and need access to finance to respond and adapt. With their governments short of funds to invest in reducing emissions and installing clean energy and sustainable infrastructure, they must supplement public spending with finance from the private sector. But the current global financial system isn’t offering them the capital they need, at prices they can afford.

Furthermore, many LMICs are struggling to service their existing loans. In 2023, half a dozen countries defaulted on payments, including Lebanon and Zambia. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), 68 countries are at risk of defaulting in 2024, including Ghana, Grenada, the Maldives and other nations particularly vulnerable to climate impacts.

As these impacts mount, LMICs risk getting into a vicious circle of debt, just when they need to invest to become more resilient.

Closing this finance gap and boosting global climate funds are focuses of the upcoming Conference of the Parties (COP) climate meeting in Baku, Azerbaijan, in November. At this ‘finance COP’, as it has been dubbed, world leaders will try to agree on the scale and sources of funding needed to support LMICs.

Extending the Sustainable Development Goals to 2050 — a road map

It is already clear that LMICs will need more funding than the US$100-billion pot that was agreed at a COP back in 2009. LMICs — excluding China — will need to quadruple their annual investments to $2.4 trillion by 2030 to meet their climate goals, according to a 2022 report from an independent high-level expert group on climate finance1. A more appropriate target — or ‘new collective quantified goal’, as it’s officially known — for raising climate finance for LMICs is set to be agreed in Baku.

Another key question that will be considered there is how to mobilize more private finance. Climate-related spending by private households, companies and financial institutions doubled between 2019–20 and 2021–22, reaching $625 billion. But 91% of this was domestic spending concentrated in high-income countries (HICs)2.

LMICs face barriers in accessing financial markets, and they borrow at higher costs than wealthier countries owing to actual and perceived economic and political risks. They often have lower credit ratings than HICs. Research suggests this is driven by, among other things, low per capita income and economic growth as well as a country’s history of defaulting on debts. Some studies also suggest3 that the way in which ratings are created is biased against LMICs, resulting in a steep increase in borrowing costs when their ratings are downgraded. For these and other reasons, in 2022 the International Energy Agency estimated that a company seeking to invest in a large solar project in Brazil or India would demand returns twice as high as they would if the project were being built in a HIC4.

Efforts are being made to reduce these investment barriers, including reforming the structure and functions of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund to improve risk assessment and make more low-cost public finance available for LMICs. But many of these efforts have yet to be fully realized.

Meanwhile, as awareness of sustainability and climate risks grows, private investors are increasingly seeking to align their portfolios with the goal of the Paris agreement to limit global average temperature to 1.5 °C above the pre-industrial average. To support this, sustainable finance standards, metrics and tools have proliferated. However, these tools were originally developed to protect investor assets from long-term sustainability risks. Some of these tools have negative unintended consequences for those seeking investment.

To illustrate, we describe here how one sustainable finance metric can create perverse incentives that might dissuade investors from supporting LMICs. And we propose another approach to avoid the risks of unintended consequences of sustainable-finance measures.

Climate risks

Governments borrow money from both public and private lenders. Private ‘sovereign-debt investors’ lend governments money in the form of bonds, bills or notes that must be repaid with interest at the end of a fixed period — six years on average for LMICs. Loans provide governments with capital in the short term, above what they collect in taxes, to spend on their policy priorities. But these loans also have repayment costs.

Ideally, governments would use their borrowed money to stimulate economic growth, allowing them to repay their debts quickly at low cost. In a climate context, for example, spending on green technologies could spur growth, or building a sea wall might reduce future climate-related losses and damages.

A gas flare at an oil-company installation in southern Nigeria.Credit: George Osodi/Panos Pictures

But the costs of servicing debts can become disproportionately high for LMICs. As of 2023, the governments of these countries owed investors around $3.9 trillion5. For example, in 2023, the average servicing costs of debt as a percentage of government revenue was 14.5% and 7.2% for low- and middle-income countries, respectively. As LMICs acquire even more debt to address climate impacts, the rising costs will limit many states’ abilities to invest in resilience.

Meanwhile, private investors, financial regulators and credit-rating agencies are paying more attention to how climate change might affect loans to countries6. This includes analysing how climate change might affect the economies of borrowing countries and their ability to meet their debt-servicing costs, as well the emissions of these nations.

Financiers are increasingly setting targets to reduce the emissions impacts of their investments. For example, financial institutions representing around 40% of global private assets have committed to reaching net-zero financed emissions by 2050.

An array of standards and frameworks has been created to evaluate the emissions and climate-risk profiles of sovereign-debt portfolios7,8. Groups developing them include the Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF), the Principles for Responsible Investment and the Net Zero Asset Owners Alliance.

Such metrics are well meaning and valuable for evaluating climate risk. But they need to be designed so as to avoid creating perverse incentives that mean investors exacerbate the climate finance gap for LMICs, as some do now.

Uneven metrics

To illustrate how perverse incentives can arise, we’ve looked at one widely used metric for measuring the level of emissions associated with a sovereign-debt portfolio — the PCAF’s Financed Emissions Standard (the Standard), the latest version of which was published in 2022. At the time of writing, PCAF has more than 500 financial institutions as members, collectively managing some $90 trillion in financial assets.

The Standard evaluates the amount of greenhouse-gas emissions released to produce $1 of gross domestic product (GDP) for each country in the investor’s portfolio — a sort of national measure of ‘emissions intensity’. It does this by assessing emissions linked to production in the country as well as its GDP, which is adjusted to account for ‘purchasing power parity’ (PPP) to support comparisons between countries on a common currency scale. For instance, imagine that a book costs 75,000 rupiah (around US$5) in Indonesia and $10 in the United States. Because it takes twice as many dollars to buy the same book in the United States as it does in Indonesia, a PPP adjustment would be applied to Indonesia’s absolute GDP to account for the different cost of living.

Will AI accelerate or delay the race to net-zero emissions?

However, LMICs are systematically disadvantaged through this emissions-intensity metric, because it focuses on production and uses the same calculation for all countries irrespective of their differences. And LMIC economies are more likely to have both lower GDPs and a higher share of GDP generated from agriculture than are HICs, whose economies are often service-based.

Agriculture — particularly small-scale and subsistence farming — generates relatively high emissions of methane and nitrous oxide, and low contributions to GDP. And it’s hard to decarbonize. Energy use — which has tended to account for a high share of emissions in HICs — also generates high emissions, but these can be more readily reduced through electrification and adopting renewable energy.

Thus, LMICs fare badly on a metric such as the Standard, because their emissions intensities are relatively high, given their low GDPs. And they are less able to change that using available technologies, owing to the structures of their economies. As such, investors pushing for more-sustainable portfolios might opt not to invest in nations with high emissions intensities.

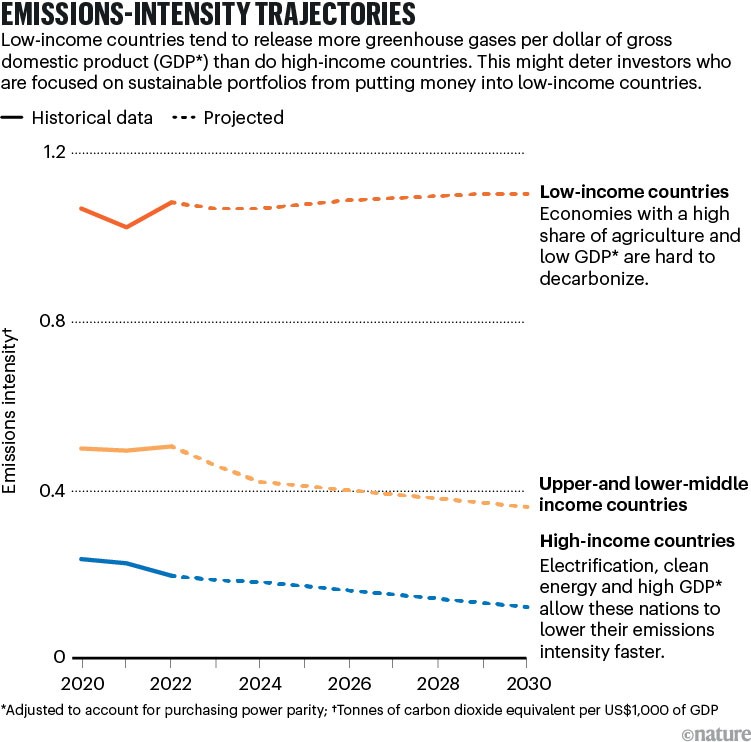

Analysing these (see ‘Emissions-intensity trajectories’), we find that emissions intensities are several times higher in most LMICs than in HICs. The 2030 emissions intensities of China and India, for example, are around five times that of the United Kingdom, and Niger’s is ten times that of the United Kingdom.

Source: Supplementary information

Moreover, differences in the make-up of economies are likely to persist for decades. Analysing the relationship between attributed emissions and country income, and projecting it to 2050, we find that the Standard will continue to heavily favour investments in HICs, even as the GDP of emerging economies increases (see Supplementary information). This is mainly because most HICs have lower emissions intensities already and targets to reach net-zero emissions by or before 2050, whereas LMICs with net-zero targets more often have goals for 2060 or later, balancing the ambition to reduce emission with their development needs.

Adjusting GDP for PPP, as is done in the Standard, mitigates some of this bias. By focusing on the buying power of a dollar in country contexts, this adjustment better reflects relative wealth across countries than does absolute GDP. In many cases, it reduces the emissions intensity by more than half in LMICs. However, the use of GDP adjusted for PPP still does not offset emissions differences that result from variations in economic structures. Thus, the methodology of the Standard doesn’t level the playing field entirely.

Another risk when applying such a metric is that it might encourage investors to divest from, or result in higher interest rates on loans to, countries that score poorly — the very nations that need green investment most.

Portfolio managers regularly use ‘negative screening’ to avoid investing in companies that have poor environmental records or lack net-zero plans. Such an approach can accelerate decarbonization in corporations9. The transition to a low-emissions future will require new companies to emerge and some high-emitting ones to fail. However, sovereign-debt investment is quite different. If investors systematically screen out countries, or if rating agencies use such standards in assessing creditworthiness, then LMIC borrowing costs will increase or their access to capital will be reduced10–12. Because climate change is driven by cumulative global emissions, this will make it harder for everyone to achieve the goals of the Paris agreement, and it will not ameliorate investors’ exposure to climate risk.

Industry leaders often recommend that sovereign-debt investors exercise care in managing their portfolios because of these challenges13. However, we think that a different approach is needed to manage climate risks.

A fresh approach

In our view, sovereign-debt investors should move away from evaluating country emissions at a single point in time. Instead, we propose that they work with researchers to develop metrics for judging sovereign-debt portfolios that are based on country-specific emissions pathways, which consider nations’ historical emissions performance and future trajectories. Such pathways are already widely used by governments and climate negotiators to evaluate whether country emissions are consistent with what is required to limit global warming to 1.5 °C 14.

Such a tailored approach would allow investors to build into their practice the principle of ‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’ acknowledged in the Paris agreement. This principle implies that countries should have different emissions-reduction obligations according to their evolving development needs and responsibility for historical emissions15.

LMICs would be allowed longer to reach net zero than would HICs. For example, a low-income country could be on a development pathway that’s consistent with 1.5 °C of global warming if its targets and emissions reductions are tracking towards net zero in 2070. But a HIC such as Australia might need them to track towards net zero by 2040.

To build a better world, stop chasing economic growth

Investors can make investment decisions by considering an ‘ambition gap’ or the extent to which a country deviates from a 1.5 °C pathway. They can allocate their capital to support countries that are meeting their ‘common but differentiated’ Paris targets, rather than inadvertently penalizing LMICs that are slower to decarbonize than HICs. This would incentivize nations to do more.

This approach also has its challenges. Assessments of 1.5 °C-aligned pathways for each country rely on assumptions about equitable sharing of the remaining emissions budget that the world can use to successfully limit warming. Whereas the methods for developing such pathways are well established, no widely agreed approach exists for designating country pathways in this way, given that nations have different views about what their fair share of the global emissions budget is.

In the absence of such an agreed approach, transparency regarding assumptions is crucial. It is also important to evaluate continually the incentives that the approaches and metrics adopted create for investors, and the likelihood that these will support rather than hinder flows of sustainable finance to LMICs.

Next steps

Sovereign-debt investors and researchers should expand their collaborations to develop country pathways, which can underpin financing decisions. Doing so transparently, with the involvement of experts who develop and assess emissions budgets and pathways for international climate negotiations, will help to foster consistency and open dialogue between governments and investors in how they are assessing their attributed emissions. Independent scientists can also assess the wide range of possible pathways for each country, each of which will imply different trade-offs between equity and emissions budgets at a global level16.

More broadly, it is important to be mindful of the unintended consequences of sustainable-finance metrics for climate finance flows to LMICs. Philanthropists, investors and researchers should form an independent group to evaluate and provide recommendations to avoid this. An announcement in September by the World Benchmarking Alliance about an initiative to involve investors and a financial regulator is a good first step, but could be expanded to include scientists and other outsiders to offer more-independent ‘friendly challenges’ for investors as the sustainable finance system evolves.

As the ‘finance COP’ approaches, it has never been more important for investors and researchers to ensure that the sustainable finance system does not inadvertently limit access to finance to those that need it most.