Hello Nature readers, would you like to get this Briefing in your inbox free every day? Sign up here.

Neurons (artist’s illustration) that affect hunger lose their ability to sense insulin when encased by a sticky scaffolding.Credit: KTSDesign/SPL

A buildup of ‘goo’ in an appetite-control centre of the brain might worsen obesity and diabetes. In mice, researchers found that the scaffolding supporting neurons that adjust sensations of hunger changed as the mice gained weight on an unhealthy diet. The result was a thick and sticky goo that prevents these neurons from processing insulin signals. When the scientists chemically slowed the goo’s formation, the mice lost weight and became more responsive to insulin. The findings may point to new drivers of metabolic conditions, but investigating whether this goo forms in humans might be difficult, says neuroscientist and co-author Garron Dodd.

China’s greenhouse-gas emissions could be about to peak, if they haven’t already. The peak would be a major climate milestone, and comes well ahead of Beijing’s pledge of peak emissions before 2030. But some researchers are uncertain about the accuracy of current peak predictions and worry that China’s road to net zero afterwards will be a challenge. Nevertheless, China’s decarbonization “could offer valuable lessons for other developing nations striving to decouple economic growth from their emissions”, says climate economist Sun Yongping.

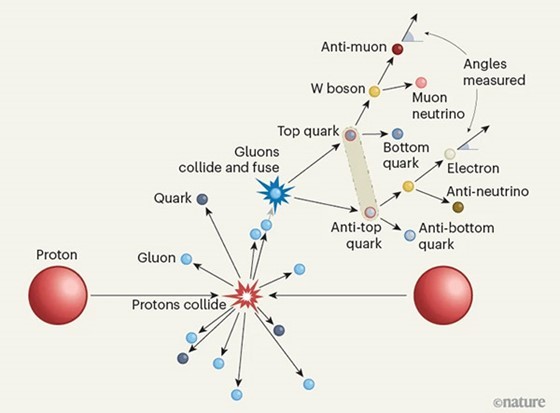

For the first time, scientists have observed quantum entanglement — a state in which particles intermingle and can’t be described separately — in fundamental particles called top quarks. Physicists had no reason to suspect that quarks wouldn’t allow themselves to be entangled, but researchers say this measurement, achieved by analysing over 1 million pairs of quarks created in collisions between protons, could pave the way for future high-energy tests of the phenomenon. “You don’t really expect to break quantum mechanics, right?”, says theoretical physicist Juan Aguilar-Saavedra. “Having an expected result must not prevent you from measuring things that are important.”

When two protons collide at high velocity, they break up into elementary particles known as quarks and gluons. If two gluons then collide, they can fuse, creating a top quark and its antiparticle, an anti-top quark. This pair decays into a bottom quark, an anti-bottom quark and two elementary particles known as W bosons. The W bosons subsequently decay into particle–neutrino pairs comprising, for instance, an electron and an anti-neutrino or an anti-muon and a muon neutrino. (Nature News & Views | 6 min read, Nature paywall)

Features & opinion

Cells in our bodies are passing delicate, time-sensitive notes to each other. These notes come in the form of messenger RNA (mRNA), which cells have to neatly package in sacs called vesicles to send between cells. This year, researchers showed that cells in all three domains of life – archaea, bacteria and eukaryotes – can send these messages, and even that they can be used as weapons between species. There are still questions to answer, such as whether other molecules packed into vesicles are necessary for mRNA’s message to land, but “it’s a fun challenge to unravel all of that”, says biologist Amy Buck. “I’ve been in awe of what RNA can do.”

Technologies that allow brain-computer interfacing could be revolutionary for individuals with severe disabilities, but they raise ethical challenges. Whether they’ll develop into highly personalized treatments or become standardized and widely available has implications on their equity, and managing public expectations of the reality of these interfaces compared to their depictions in media is vital to avoid false hope and miscommunication. As this tech moves out of the lab and into the real world, medical ethicists Anna Wexler and Ashley Feinsinger explore how their therapeutic benefit can be realized as responsibly as possible.

Nature Human Behaviour | 8 min read

Crafting science policies is important and rewarding work, say four science-policy specialists interviewed by Nature. Their jobs involve briefing global leaders on breakthrough technologies, presenting the White House’s climate agenda to the press and helping emerging economies to reduce carbon emissions without compromising their development. Getting on policymakers’ radar and building trust with government officials can be a challenge, but in a world reeling from a pandemic and grappling with climate change, science-policy advisers are needed now more than ever.

Today I’m considering what the smallest gap I would try to squeeze through is. In research published this week, scientists found that unlike dogs (and, of course, humans), cats won’t hesitate to squeeze themselves through gaps even half their width. When a gap is wide but not very tall, they stop to think, but eventually have a go at pushing themselves through.

Let us know of any gaps, small or large, in this newsletter at [email protected]

Thanks for reading,

Jacob Smith, associate editor, Nature Briefing

Want more? Sign up to our other free Nature Briefing newsletters:

• Nature Briefing: Careers — insights, advice and award-winning journalism to help you optimize your working life

• Nature Briefing: Microbiology — the most abundant living entities on our planet — microorganisms — and the role they play in health, the environment and food systems.

• Nature Briefing: Anthropocene — climate change, biodiversity, sustainability and geoengineering

• Nature Briefing: AI & Robotics — 100% written by humans, of course

• Nature Briefing: Cancer — a weekly newsletter written with cancer researchers in mind

• Nature Briefing: Translational Research — covers biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma