After Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022, the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics (IUPAP), then celebrating its 100th anniversary, issued a statement condemning the war. It noted its commitment to “embrace and promote scientific collaboration across the world as a driver for peace”.

This rhetorical relationship between science and peace is not new. Throughout history, many people have said that science is intrinsically universal, and that its supposed neutral language and methods provide common ground for transnational communication. This universalism, so the argument goes, can in turn favour peaceful relations among peoples and nations. But none of this is a given1. A book we edited, Globalizing Physics, published earlier this year, explores the many ways that physicists, both individually and collectively, navigated the rocks and whirlpools of geopolitical tensions throughout the twentieth century — sometimes successfully, sometimes less so.

Idealism and realism

The story of how, from a shaky beginning, IUPAP became an agent of international diplomacy, shows how internationalism and universalism must be nurtured by scientists in the changing cultural, economic and political situations into which they are inserted. It has lessons well beyond the boundaries of physics in the tense geopolitics of today.

IUPAP arose in the ashes of war. Soon after the end of the First World War, a movement sprung up to create international scientific unions under the umbrella of the International Research Council (IRC), with the idea of forging collaboration between nations and, indirectly, securing lasting peace. IUPAP was part of that movement. It was formally established in 1922 as an association of national physics committees. It held its first general assembly in 1923 with 16 members — 12 from Europe, plus Canada, Japan, South Africa and the United States.

‘Shut up and calculate’: how Einstein lost the battle to explain quantum reality

Things didn’t start well. For all the fine internationalist sentiment, the IRC’s statutes were shaped by punitive attitudes from France and Belgium against Germany, and were explicit about excluding the war’s defeated parties2. This exclusionary policy was particularly frustrating for IUPAP, given the central role of the German-speaking physics community in the disruptive advances in quantum physics and elsewhere of the 1920s. It resulted in IUPAP being, by the 1930s, almost totally defunct.

In 1931, the IRC became the International Council of Scientific Unions (ICSU), dropping its policy and giving more freedom to the individual scientific unions3. What could have been an opportunity to revive IUPAP was scuppered, this time by Germany. German-speaking physicists were organized into several scientific bodies, and the two most influential, the German Physical Society and the German Society for Technical Physics, could not decide who should represent them. This problem compounded with the consolidation of the Nazis in power and the emergence of the nationalistic scientific movement called Deutsche Physik (German Physics)4 in the mid-1930s.

Transatlantic shift

In 1931, the US physicist Robert Millikan assumed the IUPAP presidency. He had grand plans to give the union a purpose through the organization of conferences, particularly a large one to be held in Chicago, Illinois, in 1933. His idea was not only to promote internationalism, but also to shift the union’s focal point from Europe to the United States. The difficult economic circumstances of the Great Depression meant that his plans did not come to fruition. Together with the tensions surrounding Germany, this resulted in a widespread pessimism about the future of IUPAP.

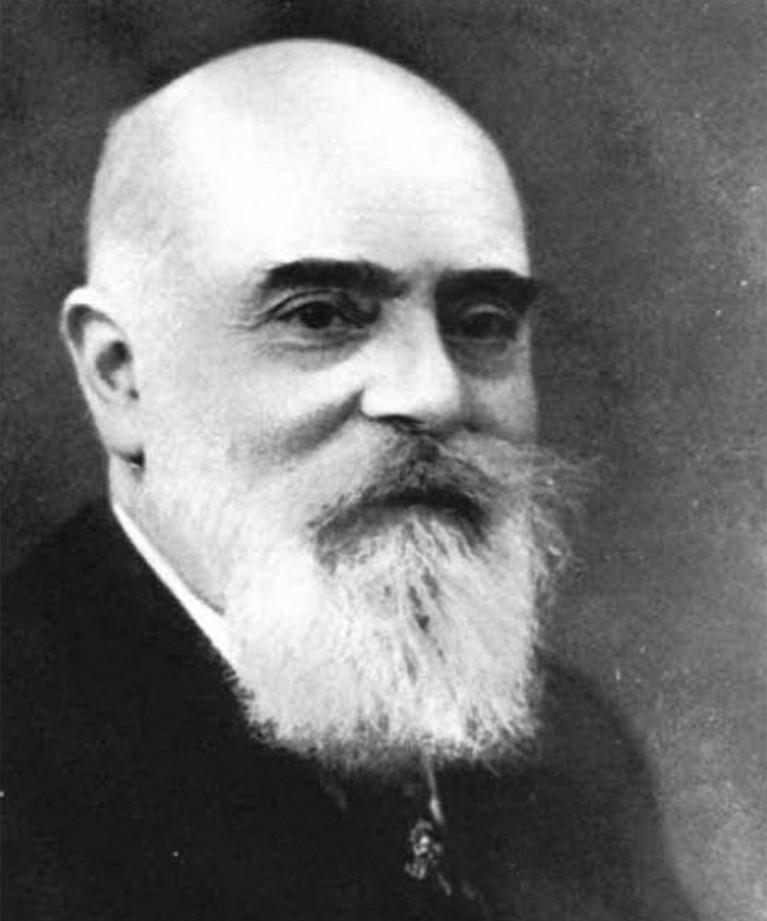

Physicist Henri Abraham (1868–1943).Credit: Volgi archive/Alamy

This wasn’t because there was no international collaboration in physics. Atomic and nuclear physics were booming as quantum theory and the theory of relativity were being consolidated and technologies such as radio broadcasting emerged. Niels Bohr, a pioneer of quantum theory whose institute in Copenhagen had been a hub of neutral internationalism during the 1920s and early 1930s, was nominated as president of IUPAP in 1934. But he turned the position down, fearing the loss of his neutral reputation were he to be associated with it.

As a tragic symbol of IUPAP’s failure to bolster international cooperation in its early years, the union’s secretary-general and probably its most active member from its inception, the French physicist Henri Abraham, was murdered in the Auschwitz concentration camp, Poland, in 1943.

Cold war diplomacy

In the aftermath of the Second World War, physicists found themselves in a transformed public and political landscape. The development and deployment of nuclear weapons had significantly altered their public image, and they were now regarded as integral to state power and security. This shift occurred in a world marked by ideological, political, economic and military competition between East and West, as well as by the onset of decolonization. Consequently, the role and purpose of IUPAP had to be reconfigured.

Learning from past mistakes, the IUPAP secretary-general in 1946–47, Paul Ewald — a German-born crystallographer who had emigrated to the United Kingdom in 1937 to escape the Nazi regime — proposed the inclusion of physicists from defeated countries as soon as possible. This led to the immediate entrance of Italy and, soon after, West Germany and Japan — West Germany even before it became a sovereign state — in the union.

The spy who flunked it: Kurt Gödel’s forgotten part in the atom-bomb story

Despite these efforts, IUPAP national members initially belonged to the Euro–Atlantic political alliance, alongside a few non-aligned countries. This was mostly owing to the isolationist policies of the Soviet Union, which began to shift only after the death of its leader Joseph Stalin and the end of the Korean War in 1953. IUPAP officials actively worked to change the situation by forging contacts with physicists from the Eastern Bloc. Nevill Mott, the UK physicist who was IUPAP’s president from 1951 to 1957, declared that involving Soviet physicists was a major goal of his presidency, and the Italian physicist Edoardo Amaldi was elected president in 1957 because it was thought that he could create favourable conditions for a Soviet national committee to join.

That did eventually happen in 1957, followed by the participation of other countries in the Soviet sphere of influence. This eastwards expansion rewrote IUPAP’s international role. Physicists began to view its meetings and commissions as valuable venues for East–West encounters during a period of tense international relations, effectively engaging in what is now termed science diplomacy5. Throughout the Cold War, IUPAP officials could not, and did not, ignore the diplomatic implications of their activities. In 1969, associate secretary-general Larkin Kerwin even announced that IUPAP’s unofficial goal was to contribute to “general international understanding”6.

Disputed delegations

Political authorities in territories whose independence was contested during the cold war were interested in joining international scientific institutions as a way to gain recognition. This issue emerged soon after the entrance of the Soviet Union. IUPAP officials had to address the ‘two-China’ problem, with parallel membership requests, first from the Chinese Physical Society in Beijing in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and the second being a US-backed request from the Chinese Physical Society in Taipei, Taiwan (the Republic of China, or ROC).

A similar issue arose with the Physical Society of the German Democratic Republic — East Germany — which applied for representation separately from West Germany. These requests had potentially disruptive political implications, depending on how the term ‘national committee’ was to be interpreted.

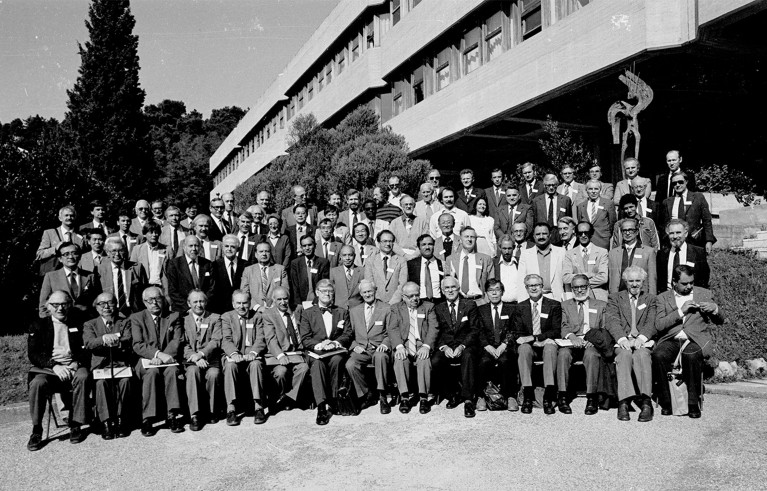

The 1984 IUPAP general assembly had delegates from two Chinese physical societies.Credit: ICTP Photo Archive/Ludovico Scrobogna

Although governments had no official voice in IUPAP management, the issues at stake here were significant for many national authorities. Many physicists sided with their governments’ agendas, but others did not. Amaldi and other IUPAP officials acted independently, advocating the immediate acceptance of all three requests by 1960. This approach aimed to show that IUPAP could overcome cold war imperatives, behaving in a balanced way. Decades later, the admission of East Germany’s physical society was recognized by IUPAP officials in letters and public statements as a pivotal moment in establishing the union’s independence from governmental influence and defining its diplomatic role. IUPAP was among the first international organizations to officially acknowledge the German Democratic Republic as a separate entity.

However, IUPAP’s assertion that admitting the East German and Taiwanese societies was politically equivalent revealed a limited understanding of the distinct contexts of the German and Chinese situations. Unlike the Germanies, both the PRC and the ROC claimed to represent all of China, complicating their simultaneous membership in IUPAP. When IUPAP officials decided to accept both of these societies, the PRC’s physical society withdrew its request. Physicists from the PRC remained excluded from the union for almost 25 years.

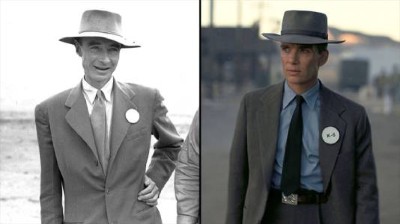

Why Oppenheimer has important lessons for scientists today

Only in 1984 did the PRC’s physical society join IUPAP, following improved relations between the PRC and the United States, but also a lot of work on IUPAP’s side over the two decades, changing statutes and officially redefining membership, with ‘national committees’ being renamed ‘liaison committees’. The final inclusion of both societies became a testament to the physicists’ ability to achieve diplomatic results parallel to, and independently of, intergovernmental diplomacy.

The recognition in the late 1950s that IUPAP also had a diplomatic function led to demands that all IUPAP-sponsored conferences be open to all physicists worldwide, regardless of their country of origin. This involved the challenging task of securing visas for scientists to travel across the Iron Curtain. Beginning with a vocal protest by IUPAP officials against a NATO-imposed ban on East German scientists, these efforts evolved into a general principle known as the Free Circulation of Scientists, which was adopted by the ICSU and all its unions. Fostering this principle became a defining task of IUPAP until the end of the cold war, and was included as one of the organization’s main aims in its 1980s statutes.

Going global

As decolonization progressed and the cold war came to an end, IUPAP sought to represent physicists worldwide by enlarging its membership beyond the cold war blocs. This renewed challenges regarding IUPAP’s identity and the relationship between physics and politics.

From its inception, IUPAP was conceived of as a union about both pure and applied physics, but the meanings and the representations of both terms changed throughout the twentieth century. During the cold war, ‘pure’ was often used as a label to rhetorically exonerate physics from its pivotal role in the arms race, suggesting that physicists could find a common ground to transcend political tensions. Concurrently, the East–West competition for scientific supremacy disregarded the increasing reliance of physicists on more complex and expensive experimental equipment that necessitated collaboration across borders.

Furthermore, the image of physics as the ‘king of the sciences’ was rapidly fading away during this period7, and the significance of the discipline in the broader network of science and technology in developing countries could not be taken for granted. Two IUPAP commissions were created to address these concerns: the Commission on Physics Education in 1960, and the Commission on Physics for Development in 1981. Both still exist.

‘Stick to the science’: Nature’s podcast series on science and politics

Initially, this was marked by patronizing attitudes from many physicists in higher-income countries, who assumed that lower-income countries could not afford, and were generally not interested in, pure science, with their needs being more aligned with practical, industrial and technological advancements.

The first two International Conferences on Physics Education co-organized by IUPAP, held in 1960 in Paris and in 1963 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, highlighted this disconnect, revealing the need to not just improve physics education, but also broaden the profession beyond a pure science practised in specialized university departments. It took several decades for more-complex views to emerge regarding the relationship between physics education and developmental issues. Eventually, IUPAP physicists reconfigured the organization’s priorities, placing greater emphasis on industrial considerations, inclusivity and aligning with the sustainability agendas promoted by the United Nations in the 2000s8.

International scientific organizations such as IUPAP have functioned effectively as instruments of science diplomacy only when their scientists have explicit awareness of their diplomatic roles. That carries lessons into the present day. One guiding principle that has shaped IUPAP’s activities since the Second World War is to stop physicists being seen merely “cog[s] in the military machine”, Ewald said. Another, emerging from its disastrous experience in the years between the first and second world wars, is the commitment to avoid any form of boycott, with the goal of fostering international collaboration and, informally, being a diplomatic channel when others are blocked.

The recent response of IUPAP to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates these principles. Although IUPAP condemned the war, it also issued a statement emphasizing the importance of keeping channels of scientific cooperation open across all political and ideological divides, and reiterating that barring scientists from scientific activity on the basis of their location is inappropriate.

There is an innate tension in these positions. Upholding them is perhaps feasible only because IUPAP does not engage in specific research projects, especially those with dual-use applications that are potentially both peaceable and non-peaceable. Lessons from IUPAP’s history might not be universally applicable, being rather specific to certain contexts of scientific cooperation and dialogue. But they do serve to illustrate an central principle: that scientific internationalism is not a given, but is the outcome of efforts from scientists both individually and collectively.