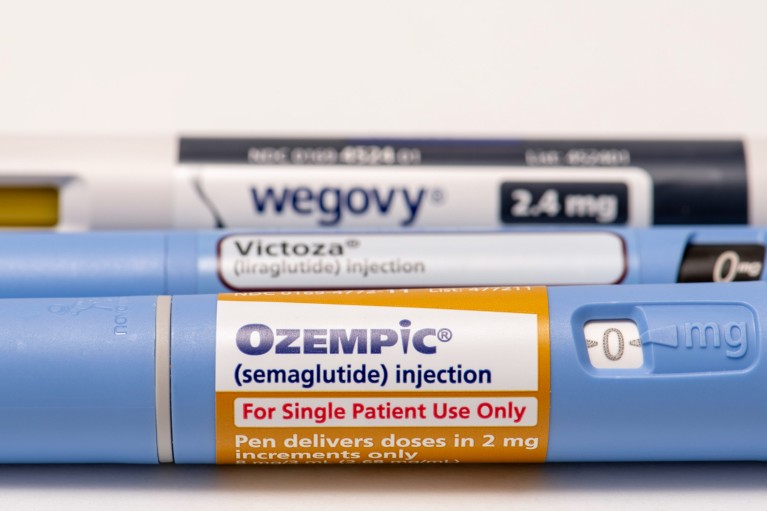

Differences are starting to emerge among the weight-loss and diabetes drugs targeting the GLP-1receptor.Credit: Michael Siluk/UCG/Universal Images Group/Getty

A host of drugs that cause impressive weight loss has transformed the treatment of obesity — and given consumers an unprecedented choice of therapies for slimming down. Now, research is beginning to reveal how these drugs might differ from one another, despite functioning in similar ways.

Semaglutide, tirzepatide and other recently developed drugs for treating obesity and metabolic disorders all work in part by mimicking a natural hormone called glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1). But studies have found that the drugs vary in their ability to prevent conditions such as type 2 diabetes1, and that some cause greater weight loss than others2. There are also differences between these drugs and an older generation of GLP-1 medications, with research hinting that some of the earlier drugs could be more effective against neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson’s disease3 than later drugs.

Understanding the differences might help physicians to better tailor treatments, says Beverly Tchang, an endocrinologist at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York City. “For example, if someone with obesity has cardiovascular disease, I am tending to reach first to semaglutide, more than tirzepatide, because we have the data,” she says, referring to a study4 that showed that semaglutide cuts the risk of severe cardiovascular events in people with such conditions. But the choice might be different for someone with sleep apnea, she says, citing a study5 in which tirzepatide reduced sleep apnea symptoms in people with obesity.

Head-to-head comparison

Among the bestselling weight-reducing drugs are semaglutide, sold as Ozempic and Wegovy, and tirzpeatide, sold as Mounjaro and Zepbound. A study published this month1 found that tirzepatide is better than semaglutide at preventing the development of type 2 diabetes in people with obesity. Another analysis2 concluded that tirzepatide was associated with greater weight loss than semaglutide in people with overweight and obesity. Researchers are now eagerly awaiting the results of a randomized controlled trial comparing semaglutide with tirzepatide for weight loss, which will provide a more definitive answer than the previous retrospective studies.

Beyond Ozempic: brand-new obesity drugs will be cheaper and more effective

Both semaglutide and tirzepatide mimic GLP-1, which is involved in blood sugar regulation and appetite suppression. This mimicry allows the drugs to activate receptors that are normally activated by GLP-1.

Tirzepatide also mimics another hormone called gastric inhibitory polypeptide (GIP), which plays a part in fat metabolism. As a result, tirzepatide activates receptors normally activated by both GLP-1 and GIP.

But it’s an oversimplification to assume that tirzepatide’s apparent higher potency is because it targets two hormones instead of one, says Tchang. Tirzepatide “doesn’t activate the GLP-1 and GIP receptors equally”, she says. Instead, the drug binds more effectively with the GIP receptor than with the GLP-1 receptor. One hypothesis is that tirzepatide’s GIP activity boosts GLP-1-induced weight loss, even though its GLP-1 receptor activation is weaker.

An experimental drug being developed by biotechnology company Amgen, based in Thousand Oaks, California, also targets receptors for both GLP-1 and GIP. But this drug, unlike tirzepatide, doesn’t activate GIP receptors. Instead, it blocks the receptors. The medication had promising weight-loss results in an early clinical study6.

Scientists are now trying to reconcile why marked weight loss is achieved both from activating the GIP and GLP-1 receptors and from activating the GLP-1 receptors and blocking the GIP receptors. “There are theories and people are working on this, but I think we should be a little humble and admit that there are still things we don’t fully understand,” says Daniel Drucker, an endocrinologist at the University of Toronto in Canada.

Saving the brain

GLP-1 drugs not only cause weight loss but also tame inflammation, which might partially explain why they have shown potential for slowing down neurodegenerative diseases. Both Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease involve brain inflammation.

In one small clinical trial, the GLP-1 drug exenatide improved symptoms of people with moderate Parkinson’s disease3. Exenatide was the first GLP-1 drug to hit the market, winning approval from the US Food and Drug Administration in 2005. A small trial of a GLP-1 drug called liraglutide slowed cognitive decline of people with mild Alzheimer’s disease by as much as 18% over the course of a year.

Anti-obesity drugs’ side effects: what we know so far

Some researchers think that the better a GLP-1 drug penetrates the brain, the better it might be at treating neurodegenerative diseases. So far, it’s not clear how far into the brain these drugs travel, but animal studies7 suggest differences between the GLP-1 medications in that regard.

Exenatide, for example, seems to cross the blood–brain barrier, a protective shield that controls which substances can enter the brain from the bloodstream. Christian Hölscher, a neuroscientist at the Henan Academy of Innovations in Medical Science in Zhengzhou, China, attributes the medication’s initial success in treating Parkinson’s disease to that ability.

He notes that a version of exenatide that was modified to last longer in the blood did not have the same success in treating Parkinson’s as the original version8. The modified version is a much larger molecule that cannot get into the brain. “That really shows how important it is to get the drug into the areas where the damage is if you want to improve and protect the neurons,” he says. He also notes that studies suggest that semaglutide cannot cross the blood–brain barrier. “So, the newest drugs on the market for diabetes are very unlikely to show very good effects in Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s.”

But other researchers don’t share this opinion. “I don’t think we have very good data correlating brain penetration with activity in neurodegenerative disease,” says Drucker.