Some of the health benefits of fasting kick in when food consumption resumes, animal experiments show.Credit: Getty

Breaking a fast carries more health benefits than the fasting itself, a study in mice shows1. After mice had abstained from food, stem cells surged to repair damage in their intestines — but only when the mice were tucking into their chow again, the study found.

But this activation of stem cells came at a price: mice were more likely to develop precancerous polyps in their intestines if they incurred a cancer-causing genetic change during the post-fasting period than if they hadn’t fasted at all.

These results, published in Nature on 21 August, show that “regeneration isn’t cost-free”, says Emmanuelle Passegué, a stem-cell biologist at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York City, who wasn’t involved in the study. “There is a dark side that is important to consider.”

Fast way to health

Researchers have been investigating the potential health benefits of fasting for decades, and there is evidence that the practice can help to delay certain diseases and lengthen lifespan in rodents. But the underlying biological mechanisms behind these benefits have been a mystery.

In 2018, Ömer Yilmaz, a stem-cell biologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, and his colleagues found that stem cells are likely to be implicated. During fasting, these cells begin burning fats rather than carbohydrates as an energy source, leading to a boost in their ability to repair damage to the intestines in mice2.

Sex, food or water? How mice decide

Yilmaz and his colleagues sought to understand how and when fasting gives rise to a surge in stem-cell activity and numbers. In their latest work, the reserachers studied three groups of mice: animals that fasted for 24 hours, those that were allowed to ‘refeed’ (resume eating for 24 hours after a 24-hour fast), and those that could eat whenever they wanted during the study.

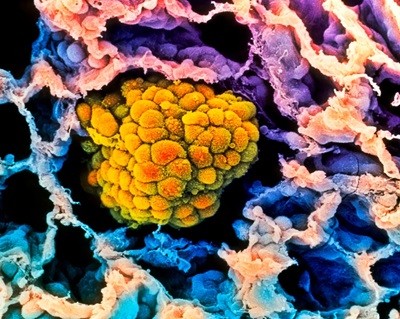

Intestinal stem cells multiplied at the fastest rate in the mice that were given food after a fast. These stem cells help to repair and regenerate the intestinal lining, in part by producing large amounts of molecules called polyamines, which are important for cells to grow and divide.

“There is so much emphasis on fasting and how long to be fasting that we’ve kind of overlooked this whole other side of the equation: what is going on in the refed state?” Yilmaz says.

Flip side

But intestinal stem cells, owing to their ability to divide constantly, can also be a source of precancerous cells. When the researchers activated a cancer-causing gene in mice during the refeeding period, the animals were more likely to develop tumours than those that didn’t fast.

It’s these extra predispositions to cancer that helped to push the animals over the edge and towards developing tumours, rather than the act of eating itself, says Nada Kalaany, a specialist in cancer metabolism at the Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts.

Why cancer risk declines sharply in old age

Researchers should always be concerned about anything that could cause cancer, but Valter Longo, a biogerontologist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, says that mice with the tweaked genes were “almost doomed to get cancer”, and that the slight rise in risk found in this study might not be applicable more broadly. For example, he points to a study3 he published in 2015 that found a 45% reduction in abnormal cell and tissue growth in mice that fasted compared with animals that did not.

Instead, Longo says that the results of the Nature study could help identify ways to perform coordinated cellular regeneration to repair damaged tissues, such as those in people with inflamed colons or Crohn’s disease.

It’s also unclear whether the findings of the Nature study apply to humans, and, if so, how. Yilmaz says that he and his colleagues plan to do a clinical trial to find out. But the findings make clear that the refeeding period creates a “vulnerable state” that might warrant extra caution against anything that could damage cellular DNA, he says.