Janice Sellers, a professional genealogist in Gresham, Oregon, has studied her family’s history for decades, and she’s uncovered a few twists along the way. In 2016, genetic testing revealed that her grandfather was not biologically related to his own father, for example. Another surprise came in 2022, when she learnt that she was related to a woman who had died at least 600 years ago and was buried in a medieval Jewish cemetery in Erfurt, Germany.

The woman’s genome had been analysed as part of an ancient-DNA study1 and uploaded to a genetic genealogy website called GEDmatch. A Jewish historian and genetic genealogist named Kevin Brook found numerous living people who shared long stretches of DNA with the fourteenth-century Erfurt woman, and contacted Sellers to let her know that she was one of them. Sellers remembers being intrigued: “I was thrilled to find out I had some DNA left from a line that can be traced back that far,” she says. “Who would have guessed?”

In the decade or so since scientists reported the first ancient human genome sequence, they have generated genome data for more than 10,000 ancient individuals. Most of these are people who lived so long ago that it’s not possible to detect meaningful links with modern individuals. But, because ancient-DNA researchers have forged closer ties with archaeologists and historians, the number of ancient human genomes from the recent past — just a few hundred years ago — has grown.

How Denisovans thrived on top of the world: mysterious ancient humans’ survival secrets revealed

Now, scientists are finding connections to modern relatives of African American ironworkers in eighteenth-century Maryland and to notable historical figures, such as Ludwig van Beethoven and the Native American leader known as Sitting Bull. Unravelling these relationships, researchers say, could provide information about historical individuals’ identities and their descendants’ subsequent migrations. Such investigations could also help to fill in the genealogical histories of people for whom such information has been obscured or erased, such as the descendants of enslaved people. It is “the next thing in the field of ancient DNA”, says Éadaoin Harney, a population geneticist at consumer-genetics firm 23andMe in Menlo Park, California. “It’s a new way to study human history.”

But the connections aren’t always meaningful or informative. And that murky reality might be lost on consumers who subscribe to genetic-testing services that offer to tell them about the DNA they share with people who lived many hundreds and even thousands of years ago, such as European Vikings or Bronze Age farmers in China. The relevance of such information can easily be misunderstood and, some researchers worry, misused. “You have to be careful how to interpret this,” says Harald Ringbauer, a computational geneticist who works on ancient DNA at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany.

From a long line

The stretch of DNA that Sellers and the Erfurt woman share — a couple of million DNA bases spanning chromosome 11 — is known as an identical by descent (IBD) segment. Consumer-genetics companies have long used IBD segments to match relatives, such as distant cousins who share a great-great-grandparent, in their databases. But for genomes older than a few hundred years, these links are less informative.

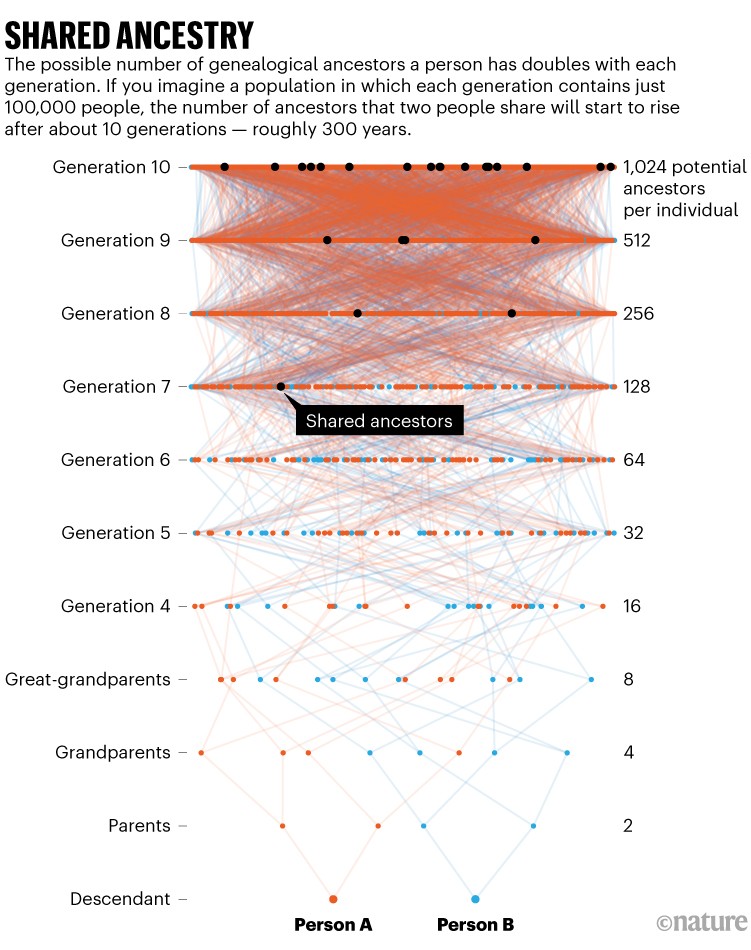

For one thing, the information is incomplete. Scientists make a distinction between genealogical ancestors, who include everyone in a family tree, and genetic ancestors — the subset of people in that tree with whom someone actually shares stretches of DNA. The potential number of genealogical ancestors a person has doubles with each generation. So going back 20 generations, or about 600 years, a person has up to one million ancestors. Add just ten more generations, and they’ve got more than one billion possible ancestors. The actual number of genealogical ancestors is much smaller, however, because people in every generation are mating with people who share common ancestors.

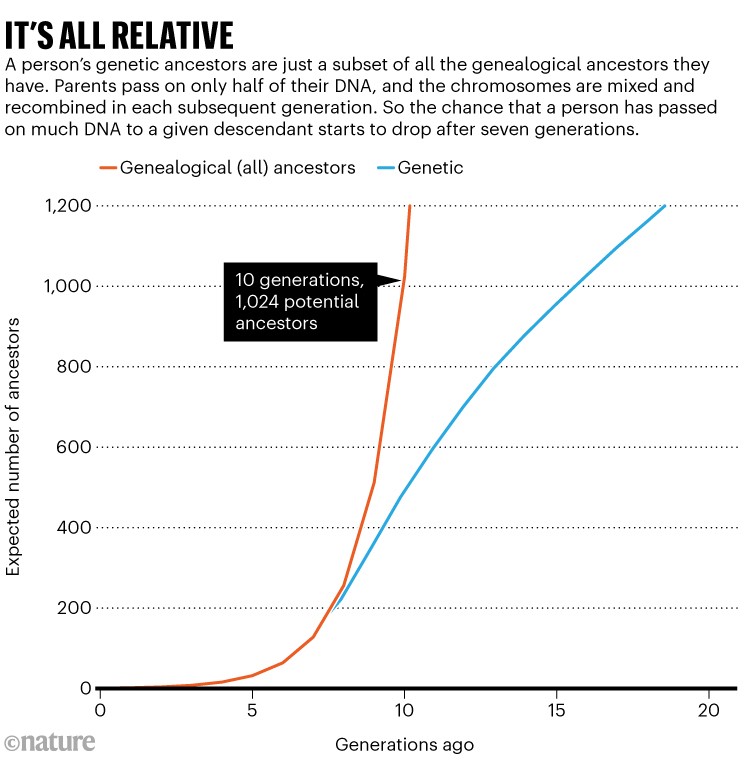

But because each parent shares only half of their genome with their child, and that half gets chopped up and redistributed with each subsequent generation, a person has fewer genetic than genealogical ancestors. They will share at least some DNA with each of their 16 great-great-grandparents. But further up the family tree, the chance that any segment of a given person’s genome will end up in a particular present-day descendant starts to fall. What gets passed along mostly comes down to chance (see ‘It’s all relative’).

Source: Graham Coop/gcbias (https://go.nature.com/3wt8tgu)

“Once you go back to very ancient times, or even the early Middle Ages, these IBD segments don’t tell you anything about genealogy,” says Shai Carmi, a population geneticist at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, who co-led the Erfurt ancient-DNA study. This is because present-day people from a particular population are all genealogically related to a medieval ancestor in highly similar ways. The Erfurt woman lived so long ago, says Carmi, that it’s likely that all Ashkenazi Jewish people alive today have a genealogical relationship to her that is similar to Sellers’. So, sharing an IBD segment is a matter of luck, with all present-day people from the population having the same odds of doing so.

Sellers knows from experience that people don’t share IBD segments with everyone in their family tree and so she didn’t expect that her ancient match indicated a close connection. “I didn’t assume it meant anything,” says Sellers, who identifies as culturally Jewish.

Exactly when IBD matches between ancient and modern people become genealogically informative isn’t completely clear, and depends on population size, mating patterns and other demographic factors. Generally speaking, however, different people from the same population can have mostly distinct family trees going back 300 or 400 years (see ‘Shared ancestry’). So, an IBD segment shared with an ancient person from this period has the potential to reveal that someone is related to them — most likely through a common ancestor who lived even longer ago, says Carmi. As population geneticist David Reich at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, puts it, “Once you get within artillery range to the present, you can actually find connections.”

Source: Graham Coop/gcbias (https://go.nature.com/3AAG9SV)

Celebrity genomics

Some of the first efforts to link ancient and modern genomes through IBD segments have been what Ringbauer calls “celebrity genomics”. The comparisons have been used to authenticate remains of famous individuals or confirm genealogical relationships. But the results are mixed. Last year, for instance, researchers analysed DNA from several locks of hair proposed to have come from the German composer Ludwig van Beethoven, who died in 1827 and had no known children2.

When they compared the genome sequence of one sample to those of three known living descendants of Beethoven’s nephew, Karl van Beethoven, the scientists were unable to detect any long IBD segments. Meanwhile, more than 600 people in a database maintained by the consumer-genetics company FamilyTreeDNA shared detectable IBD segments with the hair. Many lived in regions of Germany that were home to Beethoven’s ancestors, but even those with the longest IBD segments could not be linked to the family through genealogical records.

Ancient DNA from Maya ruins tells story of ritual human sacrifices

Researchers also investigated hair from the nineteenth-century Lakota Sioux leader Tatanka Iyotake, or Sitting Bull. In 2007, on the basis of historical records, the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC had repatriated a hair sample to the family of Ernie LaPointe, who said he was Iyotake’s great-grandson. In 2021, a team that included LaPointe confirmed the relationship by exploring IBD segments3. LaPointe and his family now hope to use this connection to have other remains thought to belong to Iyotake — currently buried in South Dakota — reinterred at a location that is more relevant to his origins and culture.

In the near future, it might be possible to connect unknown individuals to their modern relatives using ancient DNA, says Tom Booth, a bioarchaeologist at the Francis Crick Institute in London who is part of a project aiming to analyse DNA from thousands of human remains across the United Kingdom.

Known, named individuals are sometimes exhumed from cemeteries as part of development projects, for instance, and traceable descendants have been consulted over what to do with the remains, Booth says. Similar procedures could be followed with individuals who have been identified through genetics, but Booth isn’t so sure that an ancient IBD match should be grounds for making such decisions, at least not in the United Kingdom.

“The people we’re talking about lived so long ago, if they have any descendants, they’re likely to have hundreds,” Booth says. “Just because someone has established a genetic connection to a genetic relative, should they have proprietary access to them?”

Linking past and present

Identifying descendants of ancient people can help to fill in other details about the past, say scientists. Last year, Reich, Harney and their colleagues used IBD technology to identify the living relatives of 27 individuals who were buried in a Maryland cemetery connected to Catoctin Furnace, an iron forge that operated between 1776 and 19034. Until 1850, the forge relied mainly on the labour of enslaved and free African Americans. The remains were excavated in the late 1970s as part of a motorway construction project and stored at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC.

Historian Elizabeth Comer, president of the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society in Thurmont, Maryland, has long been interested in establishing a community of modern people with links to the site. But after years of scouring documents to identify living descendants, Comer and her colleagues had found just two families. Comer, who is white, sees the quest as a way of educating people about industrial slavery and the contributions of enslaved people to American prosperity. “I want people to be able to come to Catoctin and embrace it as their legacy,” she told Nature last year.

The scientists who worked with her also saw that linking past and present genomes could reveal long-lost details about people who were buried at the site. But to make those connections at scale, it was necessary to use consumer DNA databases. “It was clear that it wouldn’t be possible to do things that the Catoctin Furnace Historical Society was interested in without having access to a database like 23andMe,” says Harney.

‘Truly gobsmacked’: Ancient-human genome count surpasses 10,000

Among 23andMe’s database of nearly 9.3 million anonymized customers who have opted in to research, Harney and Reich found more than 41,000 people who shared IBD segments with individuals from the Catoctin Furnace burial. The vast majority are ‘collateral relatives’ who have a distant ancestor in common with someone who was buried at Catoctin Furnace.

But nearly 3,000 individuals shared significantly more and longer IBD segments, indicating a closer relationship. One family from southern California shared so much DNA with a woman buried at the site that its members are probably direct descendants of the individual or of a very close relative. In some cases, the researchers were able to reconstruct family trees linking 23andMe customers to individuals who were buried at Catoctin Furnace.

The research hints at the origins of some of the workers and their families. Among present-day people found to have a connection with individuals buried at the site, those with known connections to Senegal, Gambia, Angola and the Democratic Republic of the Congo tend to share the most DNA. This is consistent with historical records linking ships that transported enslaved people from these regions to Maryland and other US states.

Many of the most closely related living individuals reside in Maryland — suggesting that some people who worked at Catoctin Furnace didn’t move far when the forge transitioned to mainly having paid white workers. And the presence of small clusters of people living in the southeastern United States who share especially close genetic connections could support historical evidence that some enslaved workers were sold and transported to the south.

A consumer question

Some scientists question whether this kind of research will benefit living descendants. When the Catoctin Furnace study was published, in August 2023, none of the 23andMe customers with links to the site, including those with very close ties, had been informed of their connections by the company. But this March, the firm started giving customers the option to learn whether they shared DNA segments with nine of the individuals from the burial (those with the highest quality genome data), as well as with Beethoven, Viking-era individuals and people represented in ancient-DNA data sets from the Caribbean, Asia, southern Africa and elsewhere.

Most of these samples are too old to provide genealogically meaningful connections, says Harney. But, for the Catoctin Furnace individuals and Beethoven, the company will indicate whether people share enough DNA that it might indicate a closer genealogical connection.

Neanderthal–human baby-making was recent — and brief

For the nearly 3,000 customers who fit this category, 23andMe will provide the information without charge (other than the initial fee for analysing their DNA). But more-distant relatives and people interested in discovering other historical matches will need to pay the US$69 annual subscription fee that 23andMe charges to update customers about new discoveries, such as medically relevant genetic links.

Comer wishes that everyone who is interested in knowing about their genetic links to Catoctin Furnace could access that information freely. But she says that genetic links to African Americans who were buried at Catoctin Furnace are just one of many ways of identifying with the site and the people who lived, worked and died there. “We don’t want to leave anybody out,” she says.

Jazlyn Mooney, a population geneticist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, questions whether the team adequately sought out and listened to the concerns of people, including possible descendants, who might object to analysing the DNA of people who were enslaved and identifying living relatives. “It’s all very one-sided,” she says. “I can imagine there are a lot of people who would not be very happy who are also descendants.”

Mooney, who is African American, also has concerns about how genetic links to Catoctin Furnace could be communicated to people, and the role of a for-profit company as gatekeepers to that information. It doesn’t promote equity, she says.

Reich says that he and his colleagues listen to a variety of perspectives before going ahead with projects such as the Catoctin Furnace study, including from people who have the same kinds of misgivings as Mooney. “If that means not doing a study, which we’ve done on many occasions, so be it.”

He hopes the resulting study and an accompanying paper exploring its ethics reflect those conversations5. “We think that that’s better than just blasting ahead and not acknowledging those issues,” Reich says.

Connecting carefully

23andMe isn’t the only company that matches customers to ancient and historical individuals. And because many of the ancient-DNA data are freely available, companies can analyse them on their own and present conclusions to customers any way they wish. A firm called My True Ancestry, based in Bäch, Switzerland, looks for IBD segments in a database of thousands of ancient and historical individuals, including people buried at Catoctin Furnace, according to chief executive Markus Kangas.

Comer has received hundreds of e-mails from people who were told by My True Ancestry that they were related to individuals buried at Catoctin Furnace. But she has concerns about the accuracy of information being provided to people. She is aware of at least one discrepancy between results supplied by 23andMe and those provided by My True Ancestry.

Ancient DNA reveals the living descendants of enslaved people through 23andMe

Reich says that identifying shared IBD segments in ancient and modern genomes isn’t straightforward. Drawing IBD matches requires filling in patchy ancient-DNA sequences with modern data from a similar population, and this can lead to false negatives and positives. “There are lots of ways to go wrong,” Reich says. Regarding the methods used by My True Ancestry and others, he says, “Maybe they’re great. I don’t know. They’re not publicly available.”

Kangas, who has a background in data science, stands by the methods he developed and says the results his company provides can be confirmed with resources such as GEDmatch — but he has no plans to make the technology publicly available.

Regarding concerns about how ancient genome connections are communicated, Harney says that 23andMe tries to be careful when specifying what a link to ancient individuals actually indicates. “One of the things we really emphasize is that most of the connections we’re finding are very, very distant,” she says. “There’s a lot of people who see they share any genetic connection, they jump to ‘that’s my direct ancestor’.”

Giulia Gallio, collections and archives manager at the non-profit organization York Archaeology, UK, has seen that sort of confusion at first hand. She oversees collections that include human remains analysed for ancient-DNA studies, such as Roman-era individuals who lived around 2,000 years ago.

She has received numerous letters from people claiming to be descendants on the basis of tests from My True Ancestry and other companies. One person asked for access to a skeleton to get it 3D-printed, and a separate group wanted to hold a vigil in its collections room; she declined both requests. But, for the most part, “the enquiries were quite benign”, she says. “There was no, ‘You have to return my ancestors to me.’”

Scientists expect that the number of connections being drawn will balloon over the next few years, as researchers increase their work with publicly available collections of modern genomes, and more ancient human genomes become available. The chances of finding IBD matches increase vastly with the size of the databases, Ringbauer says. So resources such as the UK Biobank, a public repository of genome and health data from 500,000 UK residents, and the All of Us study of more than one million US residents could allow researchers to ask and answer many questions about ancient genomes.

A 2024 ancient-genome study on the effects of the Black Death in Cambridge, UK, for example, identified participants in the UK Biobank who share IBD segments with individuals who lived between 1550 and 18556.

And as these links to the past swell in number, scientists are imagining new ways of studying history. For the African Americans buried at Catoctin Furnace, Reich, Harney and their team created ‘fingerprints’ of modern ancestry — patterns of inheritance that varied from person to person. It’s not yet clear what these differences indicate, says Reich. But it’s possible that fingerprinting ancient human genomes could offer fresh insights into mobility patterns, birth rates and other facets of life. “This is a frontier for demographic research”, says Reich, that could enhance the study and understanding of both modern and ancient populations.